Abstract

This essay explores the contradictions that emerged around the use of American hallucinogens in colonial times. According to European frames of reference, the consumption of these substances was problematic, especially from a religious perspective. For this reason, on many occasions its use came to be considered a threat to Christian values and was therefore criminalized by the authorities. Although people from all social and economic backgrounds used these substances, most of the accusations of idolatry, sorcery, superstition, and witchcraft fell on Indigenous people and people of African descent. They conducted practices related to love magic, divination, the search for treasures or lost objects in a context characterized by inequality and violence. The consumption of hallucinogens can evince traces of cultural resistance as well as marks of dispossession and violence in racialized bodies.

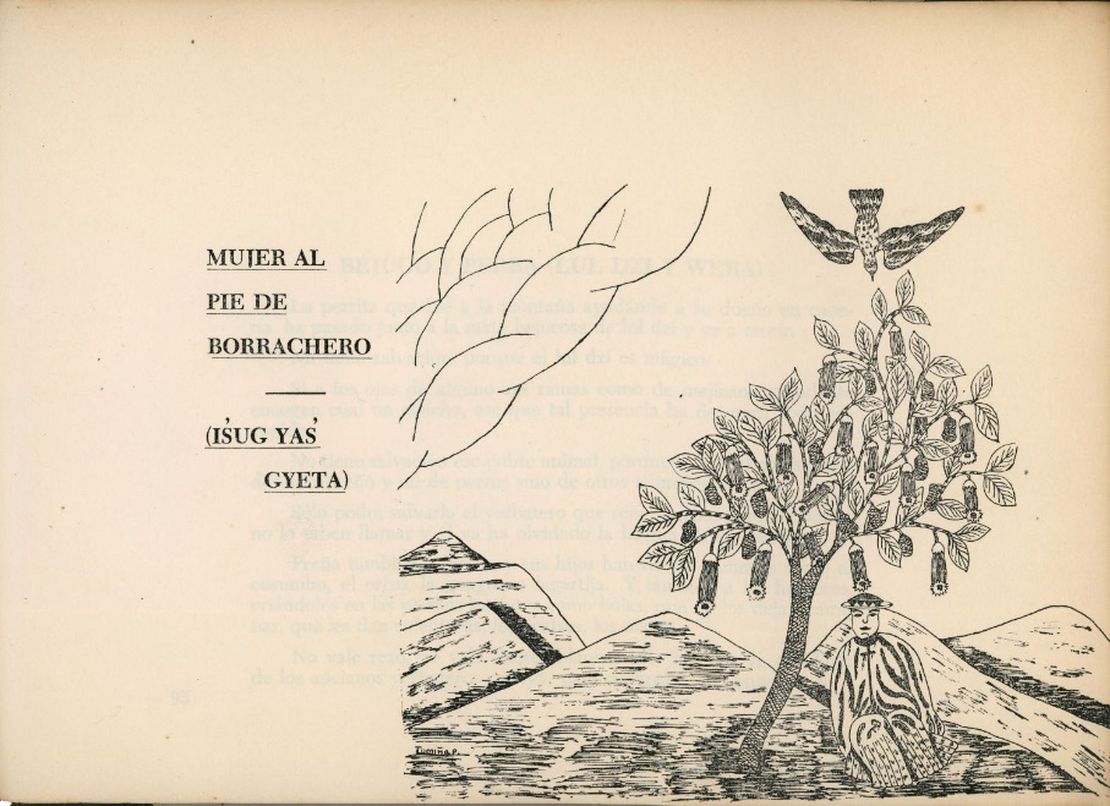

At the turn of the 17th century, in the province of Antioquia, northwestern Colombia, Pedro de Silva forced Diego Panojo, an Indigenous member of his encomienda system, to consume yerba borrachera, probably a species of the genus Brugmansia, in the hope that his visions would reveal the location of the guacas, or pre-Hispanic Indigenous burial sites, which were believed to be usually full of gold in that region.1 Silva´s ambition made him believe that Panojo´s hallucinations would help him improve his economic situation. The ritual Diego had to perform went against the progress of evangelization, a project that, at least in theory, an encomendero or head of the encomienda system was supposed to help strengthen. Instead, Silva forced an Indian who had already embraced Christianity to consume a plant that was problematic for Europeans, as the Indians had been using it to communicate with their gods before the Conquest. But Silva was not concerned or troubled by this. The knowledge, the visions and the bodies of Indians had to be aligned to satisfy their gold fever.

In Colombia, references to this type of consumption during the colonial period are scarce, and not precisely because hallucinogenic plants were irrelevant in this context.2 This absence is partly due to the Conquest dynamics. For example, in the case of ayahuasca, it is difficult to find references from the 16th and 17th centuries because the colonization of the southeast of the country —where you can still find a strong presence of Indigenous communities that consume this liana or vine— was late, and not many records have been preserved prior to the 18th century.3 Nor should we forget the little interest it has aroused in Colombian historiography. The case of Diego Panojo has only been mentioned on a couple of occasions to point out the conflicts between encomenderos and Indians in that region and to illustrate the rigorous preparation for the ingestion of the borrachero or angel´s trumpet*,* which required lengthy periods of fasting.4

This episode reveals the paradox behind the use of hallucinogens during colonial times and the perpetuation of practices believed to be superstitious and problematic for the conquistadors. The case of the Brugmansia or angel´s trumpet, far from being unique, is part of a series of processes that were undertaken across the American continent between the late 16th and early 17th centuries to eradicate or control the use of plants suspected of promoting idolatry and superstition, among which tobacco, coca and peyote stood out.

Source: Peyote (Lophophora williamsii). © Héctor M. Hernández M. https://www.tropicos.org/image/100445679.

When considering the use of hallucinogens of American origin during the 16th and 17th centuries, it is inevitable to suppose that these were rejected by Europeans and that this repulsion contributed to upholding a rhetoric inspired by religious precepts. Hence, the ban on this kind of plant is commonly presented as a merely logical consequence. But beyond the diatribes of some chroniclers and ecclesiastical debates, the fact that the use of these substances during the colonial period was not limited to Indigenous societies that were reluctant to abandon their beliefs, or to Afro-descendants in their adjustment process to the conditions the New World imposed on them, is often neglected. Contrary to this, it is possible to find cases in which even friars were investigated for smoking tobacco and for being assiduous peyote users.5 The best-known processes may be those involving Spanish, Creole and mestizo women who used these plants for a myriad of purposes related to love magic. This could lead one to think that it was something intimately related to feminine aspects, but women were not the only ones singled out for spreading superstition.

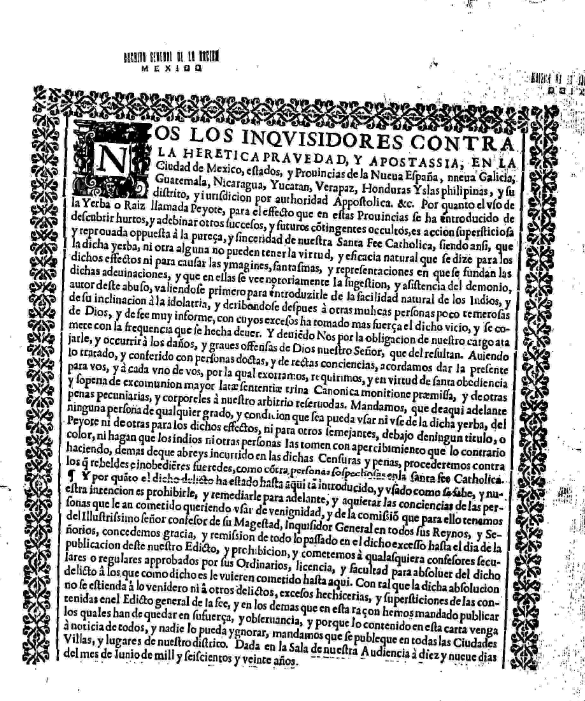

As of the 1570s, a series of initiatives were undertaken to control the advancement of evangelization among the Indigenous people, along with an examination of old and new Christians. To this end, Inquisition courts were established in America and campaigns for the extirpation of idolatries were launched. The trials involved people of all origins who —in most cases—, were accused of crimes such as superstition, witchcraft, and heresy. It was at this time that the discussions within the Hispanic or —more precisely—, Christian society surfaced. A heated debate surfaced over the appropriateness of allowing or punishing the use of American stimulants and hallucinogens.6 Civil and ecclesiastical authorities feared that the adoption of such practices by Europeans would jeopardize the pillars of their identity, based on Catholic principles.7 It was in this context that the Inquisition banned the use of peyote in New Spain: the edict enacted in 1620 gave leeway for inquisitors to threaten those who dared to continue the cactus uptake to have visions and thus “find loots, divine other events, and predict future hidden treasures.” The threats ranged from excommunication and economic sanctions to physical punishment.

Source: “Edicto del Santo Oficio condenando el uso de la yerba de peyote,” México, June 19, 1620. AGN, Ciudad de México, Inquisición, vol. 289, file. 12, f. 1r.

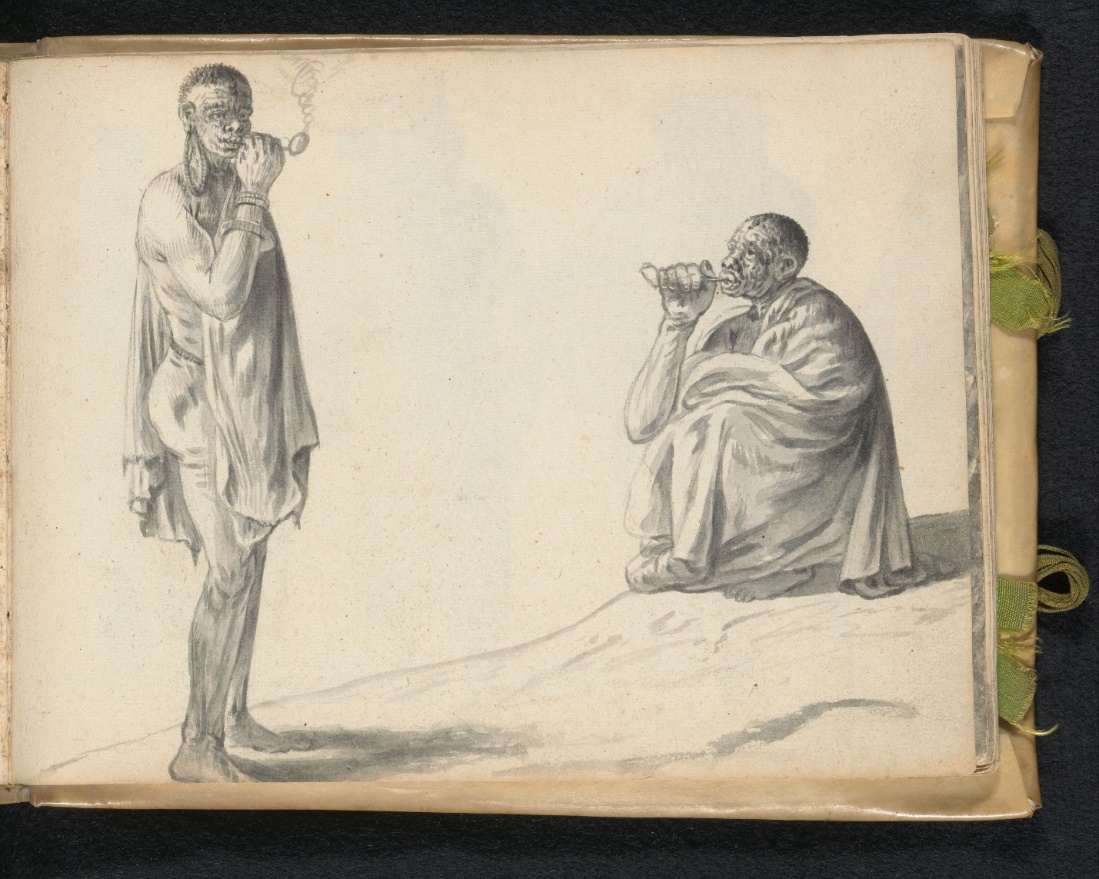

The provisions with which the Spanish monarchy and the Church sought to restrict the use of tobacco, coca or peyote were issued in the early 17th century. It is easy to be tempted to assume that they were all part of the same initiative intended to be imposed across the American territory. However, everything seems to indicate that these measures were triggered by regional dynamics. For example, between 1606 and 1614, the Spanish Crown banned tobacco farming on several Caribbean islands and in Venezuela. It is true that since the first decades of the Conquest, tobacco had generated rejection among chroniclers, who took it upon themselves to build a despicable image of smokers. This representation was intricately linked to the popular sectors: Indigenous people, slaves, and peasants, usually represented in iconography with scenes depicting the debauchery of taverns and brothels. But the motives for outlawing crops were not rooted in religious or symbolic issues. The ban moved away from the fear of moral corruption that tobacco smoke had helped spread, to get closer to a more pressing and mundane fear. It sought to stop the advance of Dutch and French pirates who came to the coasts to barter with impoverished inhabitants of those places, to exchange clothes for tobacco. Needless to say, the attempt failed. It was precisely the Dutch and the English who helped globalize tobacco by using similar tactics to those used in the Americas to secure military alliances and trade agreements.

Source: Esaias Boursse, “Two South African Khoisan men smoking a pipe,” 1662. Rijksmuseum, Ámsterdam, http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.726327.

It might seem contradictory that the Spaniards resorted to unorthodox methods to resolve everyday issues or conflicts, since these were precisely the basis of the accusations made against Indigenous peoples in the extensive literature against idolatry. Suffice it to look at the inquisitorial processes occurring in New Spain between the end of the 16th century and the first decades of the 17th century to realize that in many of them the protagonists came from diverse social and economic backgrounds. The case files depict practices considered superstitious, including the uptake of peyote to search for lost objects, to find the reasons for unrequited love, or to diminish the violent temperament of husbands, lovers, and masters. One wonders why many of the individuals accused were women of African descent.8 There may be some ground to believe they were precisely the ones needing that combination of plants and spells the most to manipulate their circumstances effectively. Perhaps, they needed this to act upon a reality they could hardly change. Namely, being subject to ill-tempered enslavers, the betrayal of their lovers, and violence. Some of them even managed to complement their expertise in the art of the supernatural with trades such as laundresses, seamstresses or midwives, which helped them buy their freedom and lead a life —thou modest— still free of those limitations. This strategy, however, did not always prove to be long-lasting. As historian Ana María Silva Campo showed, the Inquisition, in addition to condemning them to deracination and hundreds of lashes, also seized the goods they had acquired after being identified as healers, sorceresses and witches.9 From the time of accusation to the moment the ruling was issued, there was an obvious unequal criteria applied to the prosecution and punishments of Afro-descendant women. The first one built on a prejudice and the latter emerged as a new act of dispossession. It was about building an archetype of the racialized witch that served to perpetuate her condition as a poor woman.

The use of hallucinogens was not only a sign of cultural resistance on the part of Indigenous people and Afro-descendants, but also one embedded in unequal relationships rooted in the colonial society. Although in many cases the Indigenous people and Afro-descendants could receive economic compensation or some kind of status for their skills or knowledge on plants such as peyote, the angel´s trumpet, coca or tobacco, the dangers implied in the rituals cannot be underestimated and, what is worse, the persecution by the Inquisition was a burden that undeniably fell on their shoulders. The accusations and exemplary punishments showed that the seriousness of the crimes was conditioned by the social position of the person accused of breaching some moral or religious precept. Though some processes highlight that the use of hallucinogens was performed by Indigenous people and Afro-descendants, it is worth pointing out that —ultimately— the beneficiaries of the hallucinations were the Spaniards and their descendants.10

Although at first these hallucinogenic plants were intricately linked to Indigenous sources, after the Conquest, they ended up being owned, reinterpreted, and used for purposes other than those originally employed in a distinct cultural context. Healing, divining the future, changing the plans of fate, or searching for lost objects and treasures became tasks imposed on Indigenous peoples and Afro-descendants. Many of these were situations where they served the needs of others and were forced to conduct these tasks against their will, as is the case of Diego Panojo and the angel´s trumpet. The use of hallucinogens evinces how the structure of inequality and violence dynamics of colonial society worked. While Europeans sought new ways to confront their reality by acquiring a taste for what they were initially supposed to reject, they relied on Indigenous knowledge and the vulnerability of both enslaved and free Afro-descendants to build and perpetuate a negative image of racialized bodies.

Archivo General de la Nación (AGNC), Bogotá, Colonia, Visitas Antioquia, Tomo III, Titiribí y Ebéjico. ↩︎

The Brugmansia or angel´s trumpet continues to be recognized, although not precisely for its commercial significance or for the central place it occupies among the country’s Indigenous people, but because scopolamine is the protagonist of street assaults. John Slater, “Drugs, Magic, Coercion, and Consent: From María de Zayas to the ‘World’s Scariest Drug’”, Reconsidering Early Modern Spanish Literature through Mass and Popular Culture: Contemporizing the Classics for the Classroom, Coords. Bonnie Gasior and Mindy E. Badía (Newark: Juan de la Cuesta, 2021), p. 284. ↩︎

Martin Nesvig signalled the difficulty in finding references to ayahuasca consumption in colonial times. Martin Nesvig, “Forbidden Drugs of the Colonial Americas,” The Oxford Handbook of Global Drug History, coord. Paul Gootenberg (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022), p. 166. ↩︎

Mauricio Alejandro Gómez Gómez, Del chontal al ladino: hispanización de los indios de Antioquia según la visita de Francisco de Herrera Campuzano, 1614-1616 (Medellín: Fondo Editorial FCSH, 2015), pp. 79 y 129; Gregorio Saldarriaga, Alimentación e identidades en el Nuevo Reino de Granada, siglos XVI y XVII (Bogotá: Ministerio de Cultura, 2012), pp. 169-170. ↩︎

“Proceso contra Fray Pedro de Olmos, sacerdote profeso franciscano, por blasfemo”, México, 1586. Archivo General de la Nación (AGNM), Ciudad de México, Inquisición, vol. 140, file. 1, 70 ff. ↩︎

For example, the debates surrounding coca consumption in the viceroyalty of Peru. Please, see Paulina Numhauser, Mujeres indias y señores de la coca. Potosí y Cuzco en el siglo XVI (Madrid: Cátedra, 2005); Ana Sánchez, “El talismán del diablo. La inquisición frente al consumo de coca: (Lima, siglo XVII)”, Revista de la Inquisición 6 (1997): 139-162. ↩︎

Even chocolate came under suspicion. Please, see Marcy Norton, Sacred Gifts, Profane Pleasures. A History of Tobacco and Chocolate in the Atlantic World (Nueva York: Cornell University Press, 2008); María Águeda Méndez, “Una relación conflictiva: la Inquisición novohispana y el chocolate”, Caravelle 71 (1998): 9-21. ↩︎

Joan Bristol y Matthew Restall, “Potions and Perils: Love Magic in Seventeenth Century Afro-Mexico and Afro-Yucatan”, Black Mexico: Race and Society from Colonial to Modern Times, eds. Ben Vinson y Matthew Restall (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2009); Joan Bristol, “Ana de Vega, Seventeenth-Century Afro-Mexican Healer”, The Human Tradition in Colonial Latin America, ed. Kenneth J. Andrien (Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2013). ↩︎

Ana María Silva Campo, “Fragile fortunes: Afrodescendant women, witchcraft, and the remaking of urban Cartagena”, Colonial Latin American Review 30.2 (2021): 197-213, doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10609164.2021.1912481. ↩︎

Martin Nesvig, “Sandcastles of the Mind: Hallucinogens and Cultural Memory,” Substance and Seduction. Ingested Commodities in Early Modern Mesoamerica, eds. Stacey Schwartzkopf y Kathryn E. Sampeck. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2017). ↩︎