Abstract

The Guajira Peninsula has been the site of territorial and cultural conflict for centuries. During colonial times and the first decades of republican life, the Peninsula fluctuated between periods of relative tranquility and times of intense warfare and unrest. During the second half of the 18th century, the Wayúu1 and Cocina Indigenous peoples endured continuous raids and incursions into their territories. These attacks were planned and carried out by Spanish officials, and later on, in the 19th century, by Colombian and Venezuelan authorities.2 Partly because of this incessant violence, the Cocina people were eventually decimated in the 19th century.3 In the last few decades, the Wayúu have suffered violence, massacres, displacement, and confinement as they have found themselves in the middle of the Colombian armed conflict. In the present, the Wayúu people struggle against the expansion of mining and energy projects in their traditional and sacred territories. Maps from different historical periods show us this history of violence and territorial dispossession in La Guajira at the same time that they bring to light moments of Indigenous peoples’ resistance.

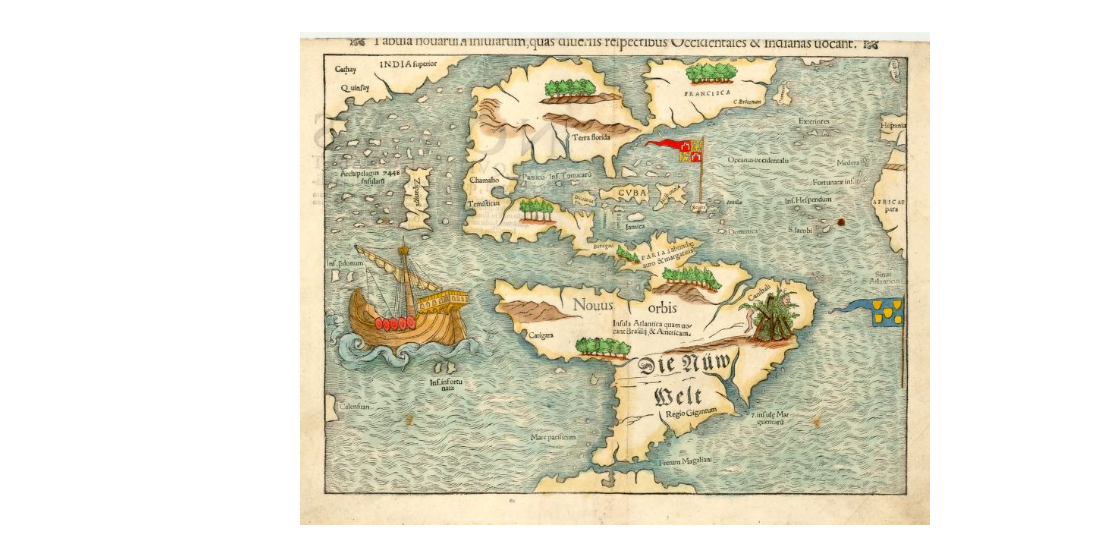

1500s and 1600s maps: Some of the first maps of the Americas to represent the Guajira do so in a somewhat distorted way. For instance, Sebastian Münster’s 1550 Tabula Novarum Insularum (see fig. 2) presents northern South America, including the Guajira, as an enormous peninsula.

Figure 2. Sebastian Münster, Tabula Novarum Insularum, Quas Diversis Respectibus Occidentales & Indianas uocant (1550, Basle).

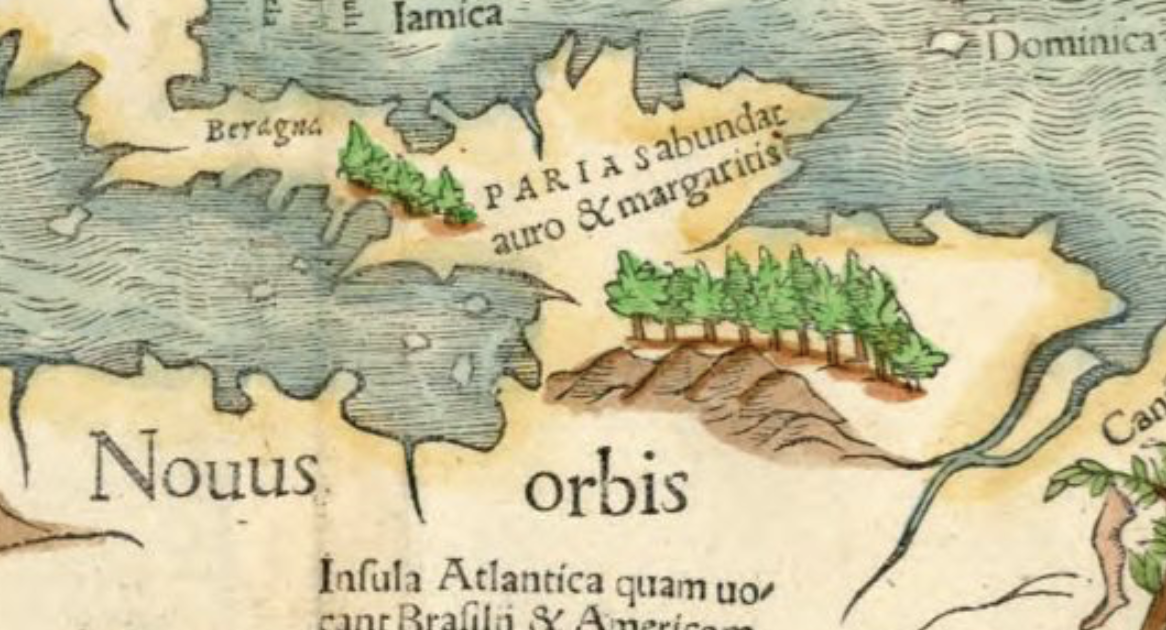

Figure 3. Detail of the Guajira Peninsula in Sebastian Münster, Tabula Novarum Insularum, Quas Diversis Respectibus Occidentales & Indianas uocant (1550, Basle).

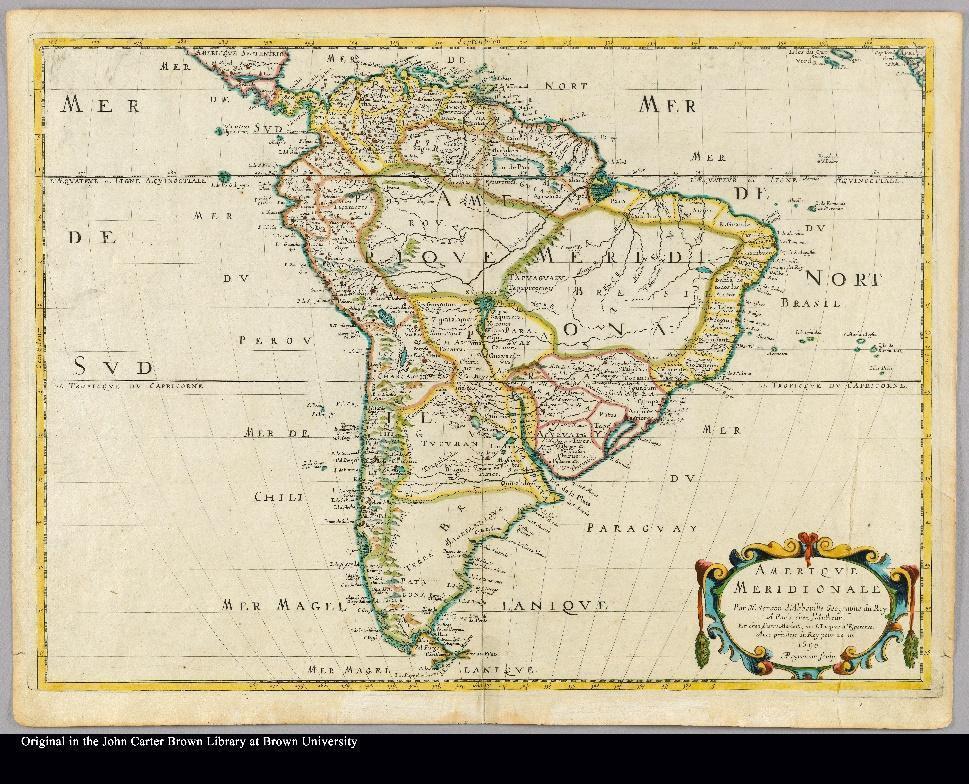

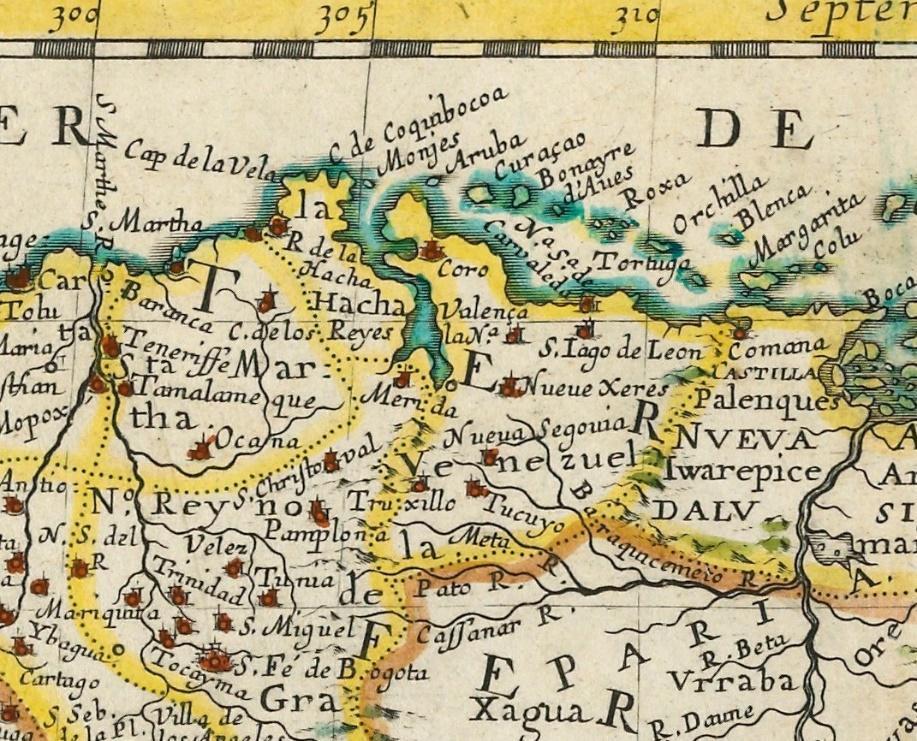

Others, such as Gerhard Mercator, Hendrik Hondius, and Jodocus Hondius’ 1623 America Meridionalis (see fig. 4),4 show La Guajira as a small tip:

Figure 4. Gerhard Mercator, Jodocus Hondius, and Hendrik Hondius, America Meridionalis (1623, Amsterdam).

Figure 5. Detail of the Guajira Peninsula in Gerhard Mercator, Jodocus Hondius, and Hendrik Hondius, America Meridionalis (1623, Amsterdam).

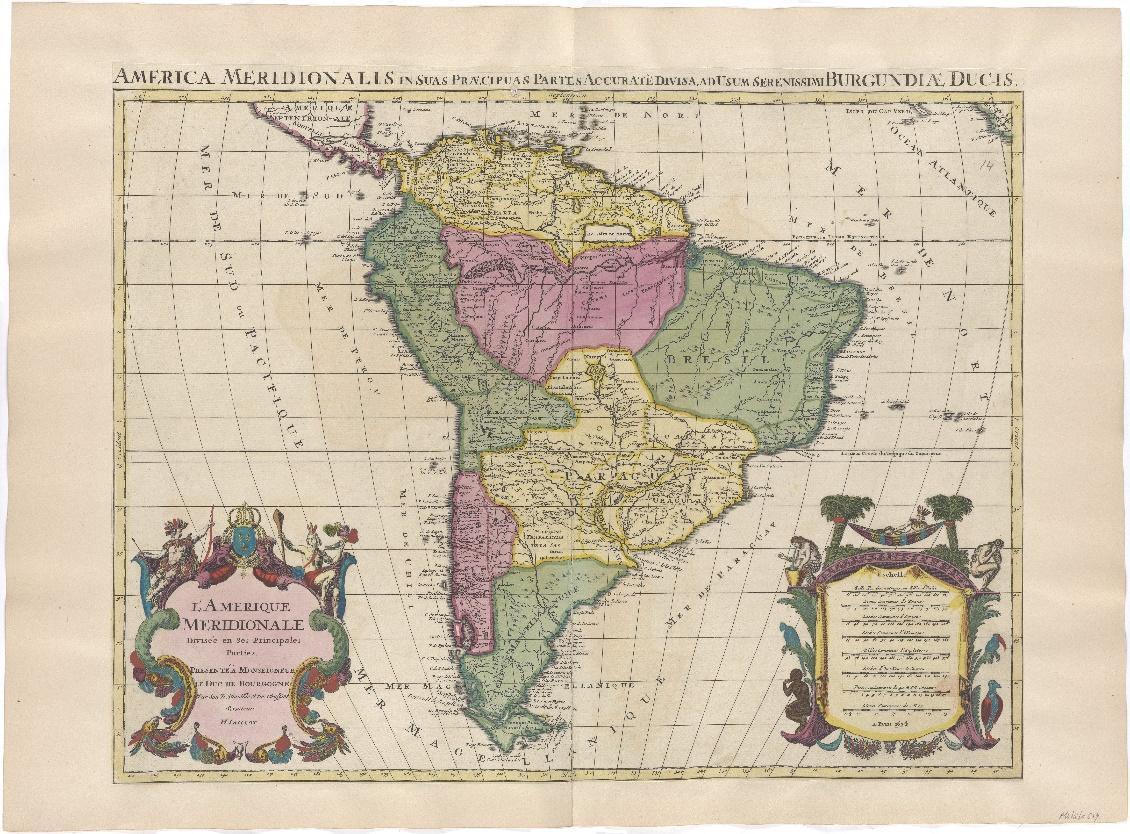

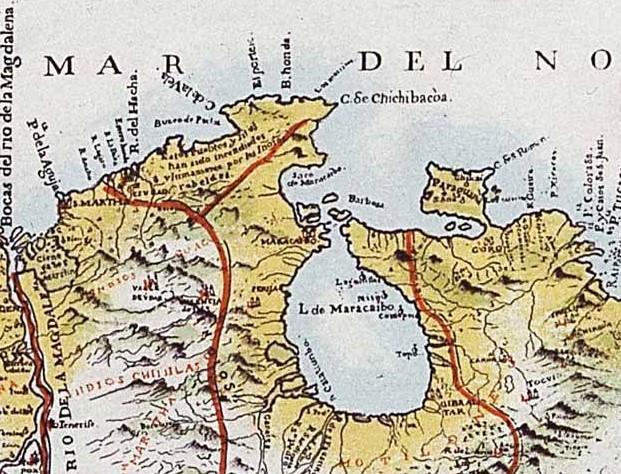

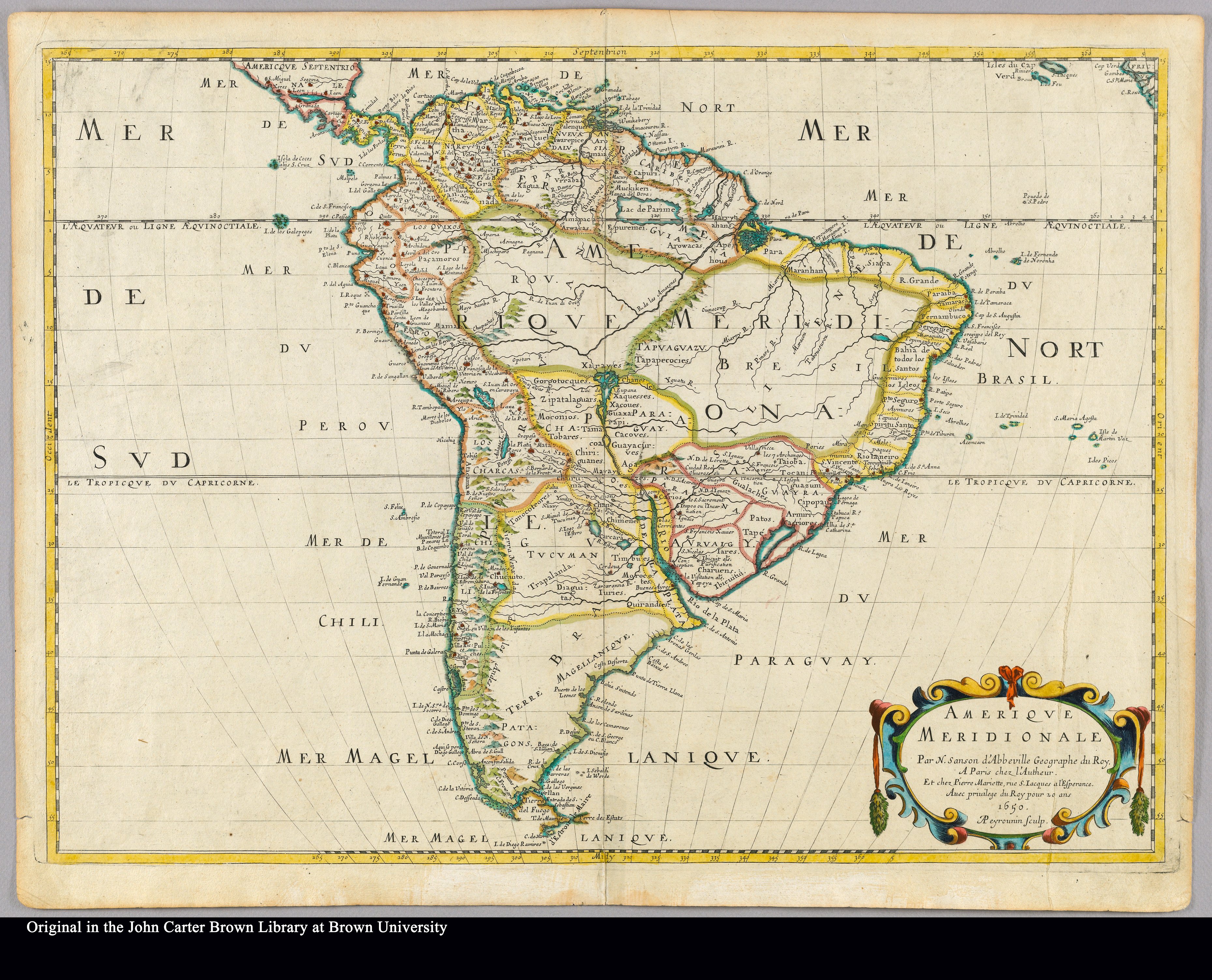

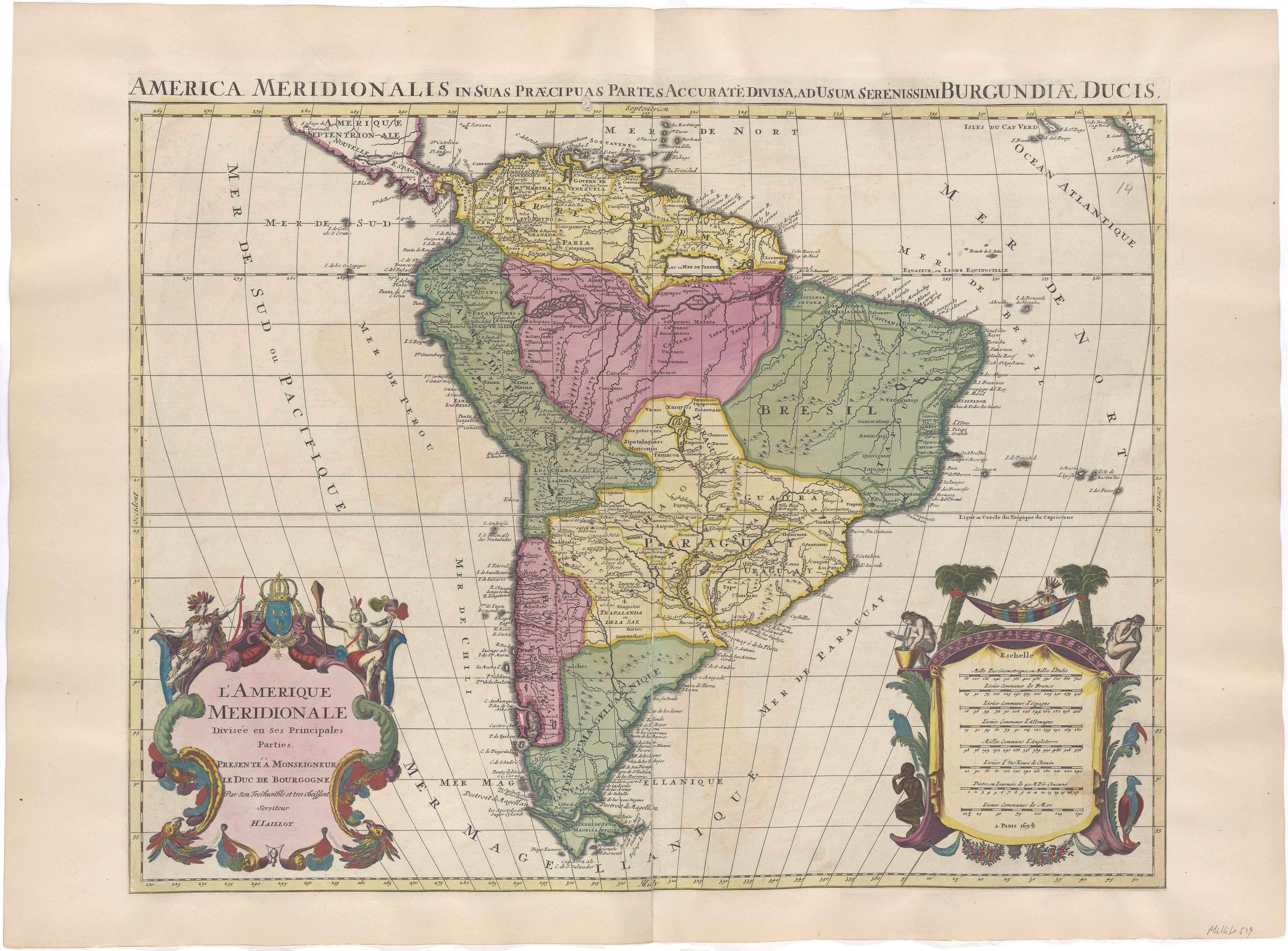

Regardless of the shape and form given to the Peninsula, these maps do not refer to the Indigenous people living in the Guajira Peninsula. Hondius’ 1623 map, for instance, only mentions the Spanish settlement of Portete. In the second half of the 16th century, other maps such as Nicolas Sanson d’Abbeville’s 1650 Amerique Meridionale (see figs. 6, 7) and Alexis Hubert Jalliot’s 1697 L’Amerique Meridionale Divisée en ses Principales Parties (see figs. 8, 9), allude to the city of Rio de la Hacha and the “Governación de Rio de la Hacha,” but not to the Indigenous peoples living there.

Figure 6. Nicolas Sanson d’Abbeville, Amerique Meridionale (1650, Paris). Read more

Figure 7. Detail of the Guajira Peninsula in Sanson d’Abbeville, Amerique Meridionale.

Figure 8. Alexis Hubert Jaillot, L’Amerique Meridionale Divisée en ses Principales Parties. Presenté à Monseigneur le Duc de Bourgogne (1697). Read more

Figure 9. Detail of the Guajira Peninsula in Jaillot, L’Amerique Meridionale Divisée en ses Principales Parties.

1700s maps and Indigenous uprising of 1769–72: It was only until the second half of the 18th century that European maps began to represent the Indigenous peoples of La Guajira and their territories in a more systematic way. This was so for a variety of reasons. First, throughout the 18th century, there was a remarkable growth in the production of maps in Europe and in the Spanish American world. Moreover, the maps produced at the time became ever more detailed. They showed the location of numerous cities, towns, Indigenous settlements, natural resources, and routes at the same time that they offered diverse topographic information and navigation data.5

Second, by the mid-18th century, the Guajira Peninsula had not been fully conquered by the Spanish Crown. Throughout the first centuries of the colonial period, Cocinas and Wayúus’ fierce resistance to subjugation was coupled with the Peninsula’s desertic and difficult terrain that made any Spanish effort to conquer the Indigenous peoples of the Guajira almost hopeless.6 Partly due to this situation, around the second half of the 18th century, the Guajira Peninsula found itself mired in intra-European conflicts. Frictions between the Spanish and British Crowns, primarily, but also between the Spanish, French, and Dutch monarchies found their way into the Guajira. For instance, the British — and to a lesser extent the Dutch and French — tried to use the Guajira Peninsula to smuggle goods into and out of New Granada and Venezuela while also using the Peninsula as a post from which they could attack and raid the Spanish fleet and Spanish ports through the Caribbean coast. In their efforts to do so, these European powers reached tacit alliances with the Indigenous peoples of the Guajira.7

Officials in the Iberian Peninsula, Santafé de Bogotá, Cartagena de Indias, and Santa Marta found this situation unacceptable and sought to subdue the Guajira and put it under Spanish control. Their goal was to conquer and evangelize the Peninsula’s Indigenous people and to fortify the Caribbean Coast to protect it from foreign intruders. Thus, throughout the second half of the 18th century, there were multiple military incursions against the Wayúu and Cocina. At the same time, Capuchin missions expanded throughout the Peninsula.8 Many Wayúu were captured and forced to work in the construction of military forts along the Caribbean Coast. Amidst this atmosphere of turmoil, Spanish, criollo, and mestizo settlers took the opportunity to steal Indigenous livestock, ransack their settlements, and take over the exploitation of pearls and contraband trade that Indigenous communities used to control. Other Guajira Indigenous people suffered all sorts of abuses on behalf of the Capuchin missionaries. As a result of this situation, there was a great Indigenous uprising between 1769 and 1772.9

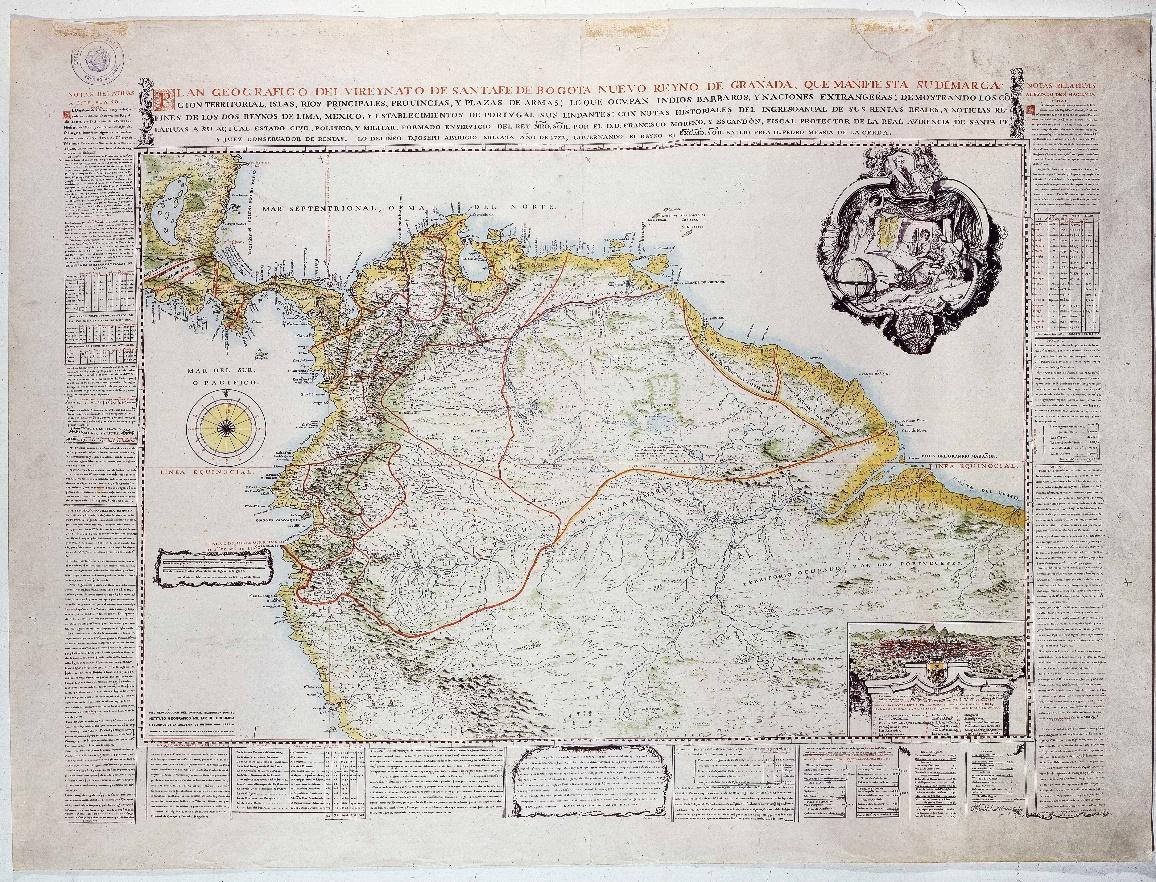

The maps produced at the time show us the Spanish authorities’ efforts to subdue the Guajira as well as the violence and dispossession such campaigns produced among the region’s Indigenous peoples. One of the first maps to explicitly mention the Indigenous people of the Guajira and to bring up the conflict that exploded in the late 1760s is Francisco Moreno y Escandón’s 1772 Plan geográfico del virreinato de Santa Fe de Bogotá (see fig. 10).10 The map explains that “towns and places [in the Guajira] have been recently burned down by the rebel Indians.”11 Although the map simply refers to the Indigenous peoples as “rebel Indians”, on the southern part of the Peninsula there is a reference to the “Indios Guag.” This was possibly a spelling error as the text should have probably said “Indios Guagiros.” This toponomy (“Guajiro”) was used to refer to the Wayúu people. Also, the “Indios Guag” text was placed in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta region, just a bit south of the Guajira Peninsula.

Figure 10. José Aparicio Morato and Francisco Moreno y Escandón, Plan geográfico del virreinato de Santa Fe de Bogotá (1772). Read more

Figure 11. Detail of the Guajira Peninsula in Aparicio Morata and Moreno y Escandón, Plan geográfico del virreinato de Santa Fe de Bogotá.

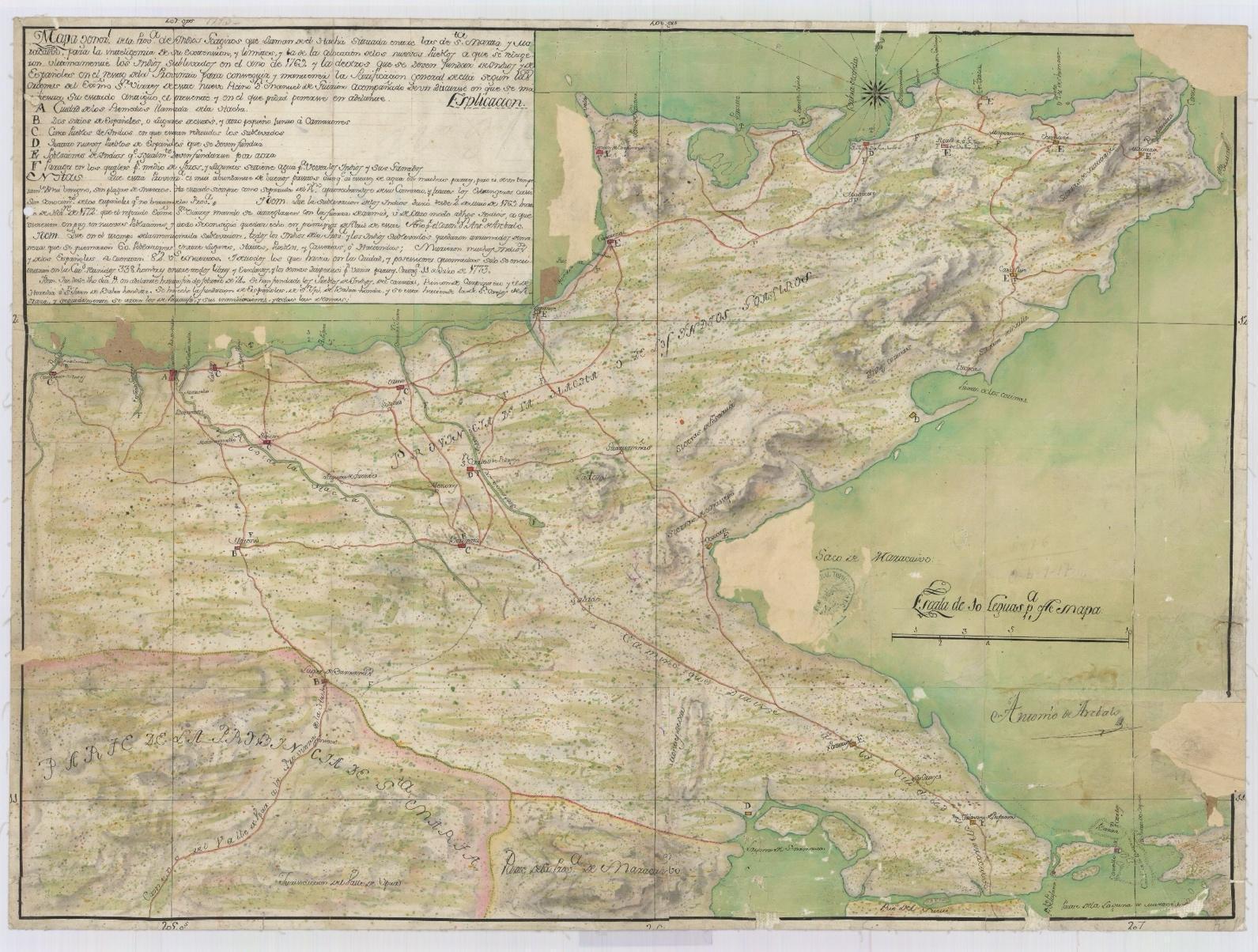

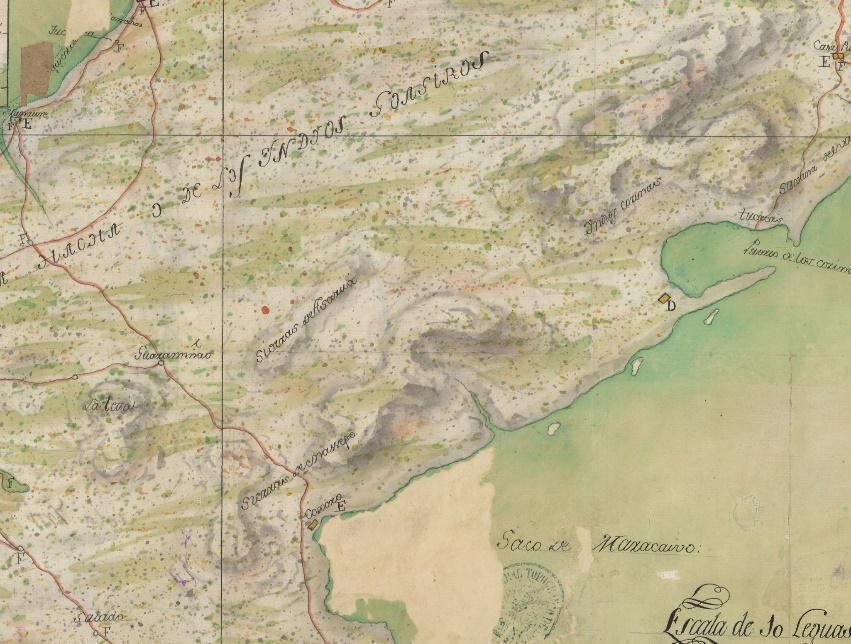

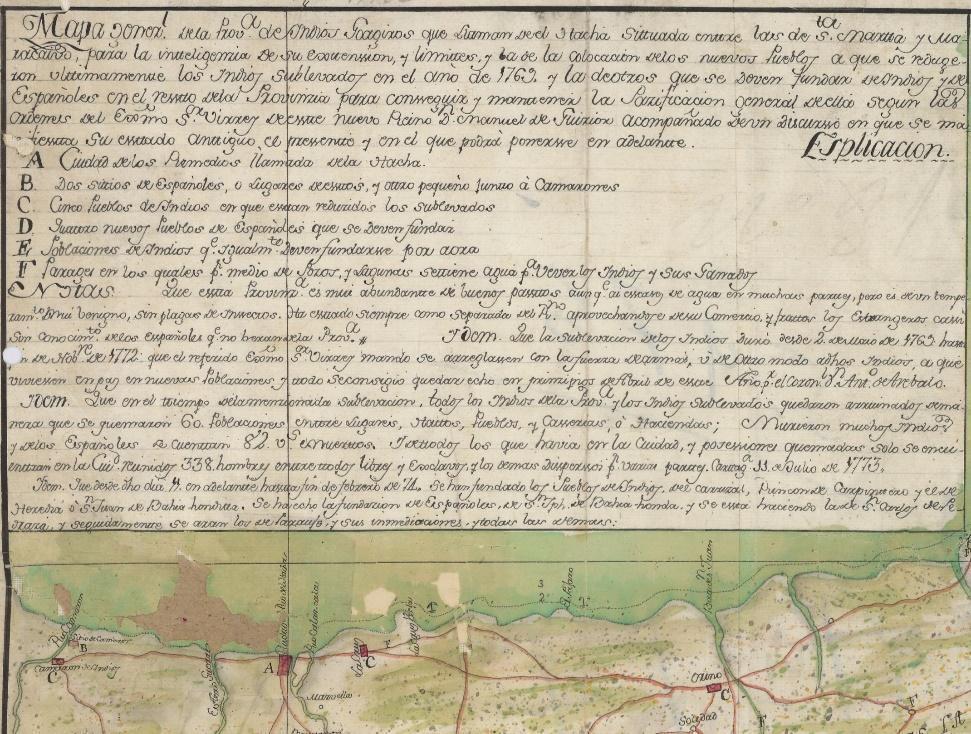

Antonio de Arévalo’s 1773 Mapa general de la provincia de indios goagiros que llaman del Hacha (see fig. 12) presents a much more dramatic situation. Even though the title of the map (“Provincia de indios goagiros”) as well as the text written on the map implicitly recognizes that the “Yndios Goagiros” and “Yndios Cocinas” controlled parts of the Peninsula, the text on the top-left present a different story. For instance, the letter C in the map refers to settlements in which the rebel Indians have been “reduced”. But the most unequivocal account of the violence being exerted comes in the bottom part of the explanation. The text explains that the revolt came to an end in November of 1772 following the Viceroy’s orders to put down the uprising through force and to move the peaceful Indians to new settlements. As the map narrates, “in times of the aforementioned revolt, all the Indians of the Province and the rebel Indians were left ruined, as 60 settlements were burned down…; Many Indians died and among the Spaniards there were 82 dead people.”12

Figure 12. Antonio de Arévalo, Mapa general de la provincia de indios guagiros que llaman del Hacha (1773, Cartagena de Indias). Read more

Figure 13. Detail of the Guajira Peninsula in Arévalo, Mapa general de la provincia de indios guagiros que llaman del Hacha.

Figure 14. Explanatory text in Arévalo, Mapa general de la provincia de indios guagiros que llaman del Hacha.

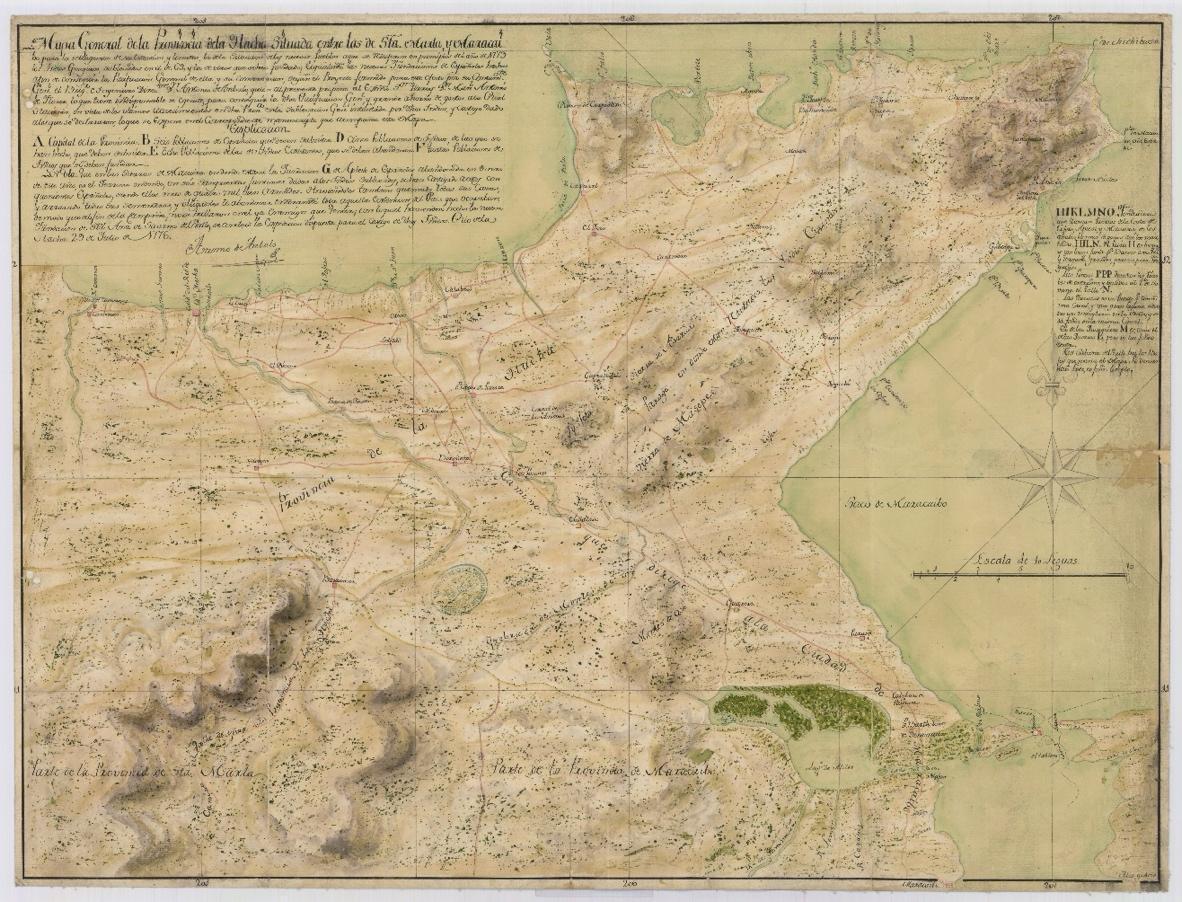

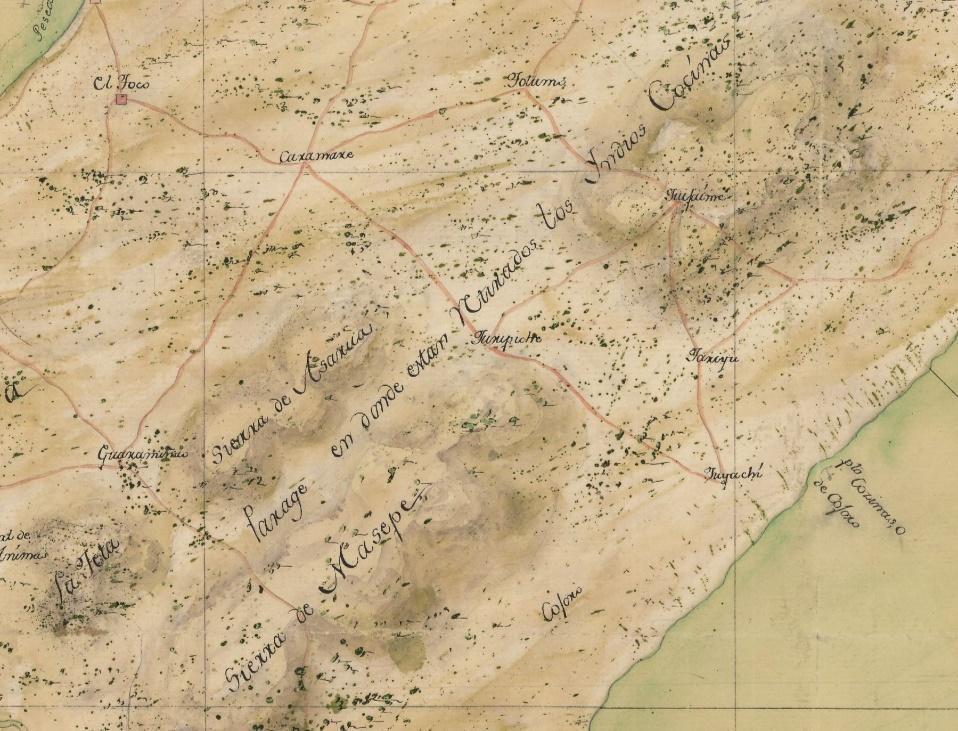

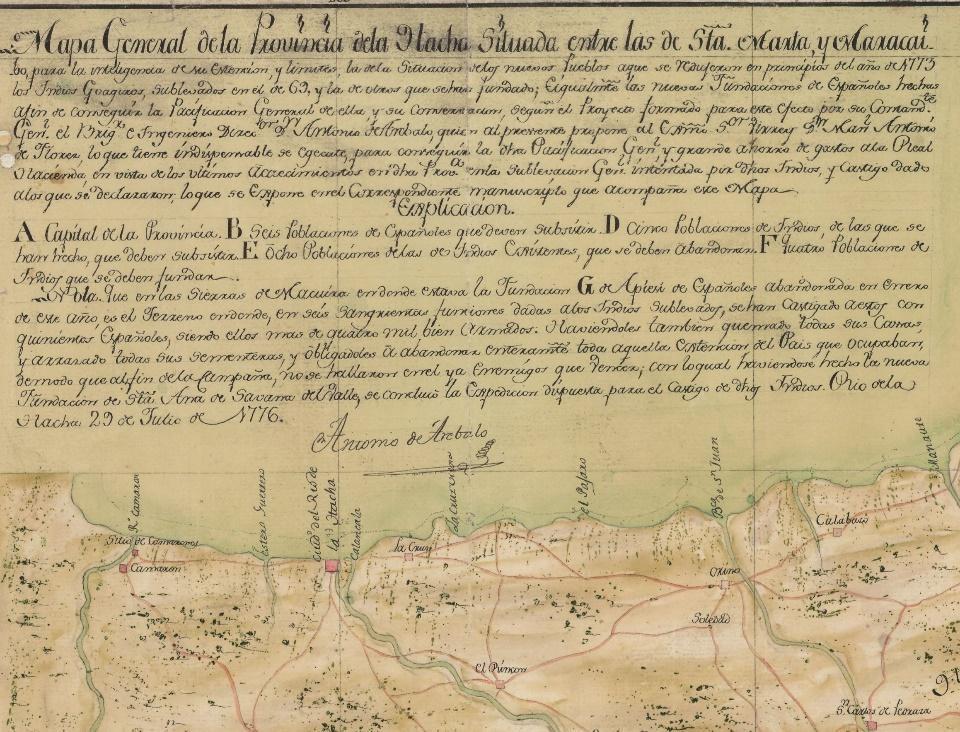

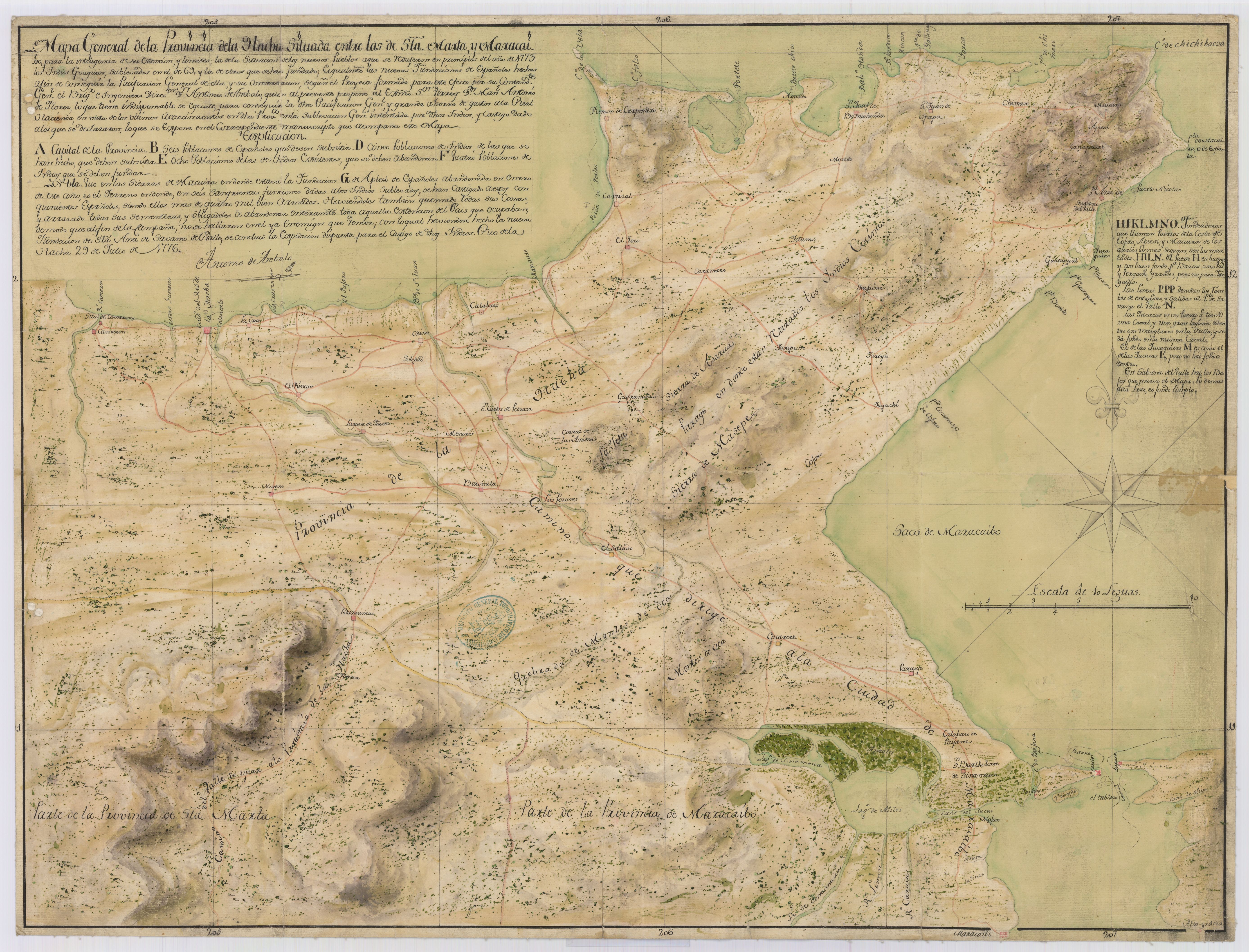

Another of Arévalo’s maps, the 1776 Mapa general de la Provincia de la Hacha (see fig. 15), gives us further details about the aggressions committed against the Indigenous people of the Guajira. The map defines a relatively large territory in the middle of the Peninsula as the “area where the Yndios Cocina have withdrawn.” The map includes an explanatory text that offers additional details. Letter “E” refers to existing Indigenous settlements that will have to be “abandoned,” and further down, an additional note explains that “the Mountains of Macuira… were the site in which, in six bloody acts against the rebel Indians, these have been punished by five hundred Spaniards, being the Indians over four thousand well-armed. Having burned all their homes and leveled all their crop fields, forcing them to abandon completely all that extension of the country, in such a way that at the end of the campaign, there were no more enemies left to defeat.”13

Figure 15. Antonio de Arévalo, Mapa general de la Provincia de la Hacha: Situada entre las de Sta. Marta, y Maracaibo para inteligencia de su Estención y límites, (1776, Rio de la Hacha). Read more

Figure 16. Detail of the Guajira Peninsula in Arévalo, Mapa general de la Provincia de la Hacha.

Figure 17. Explanatory text in Arévalo, Mapa general de la Provincia de la Hacha.

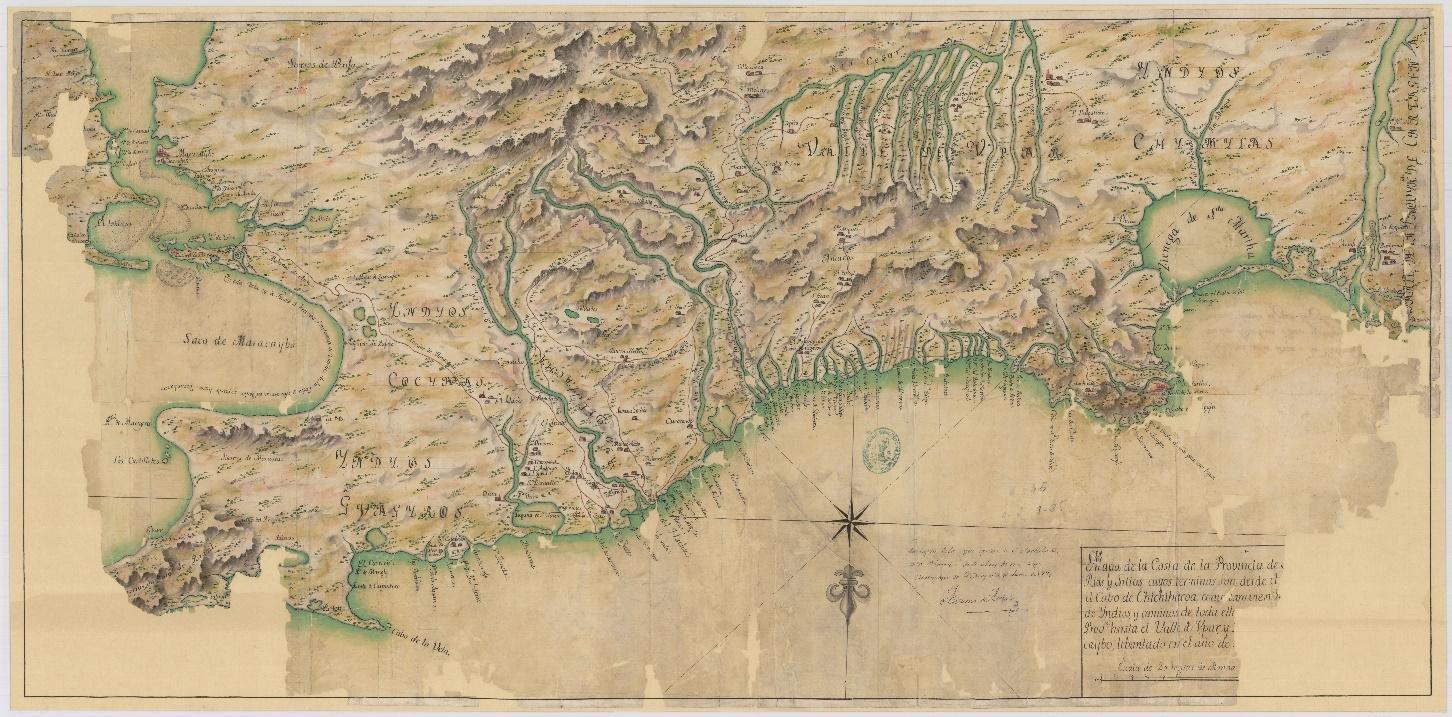

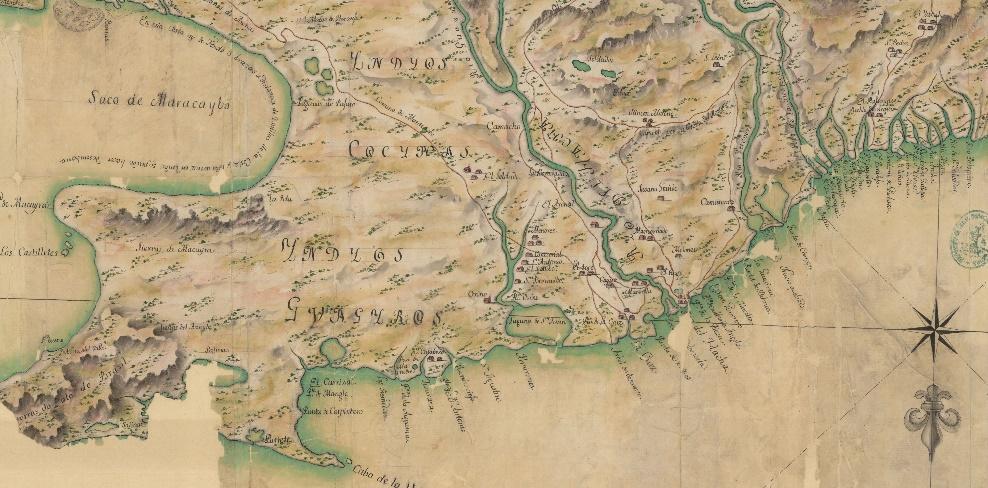

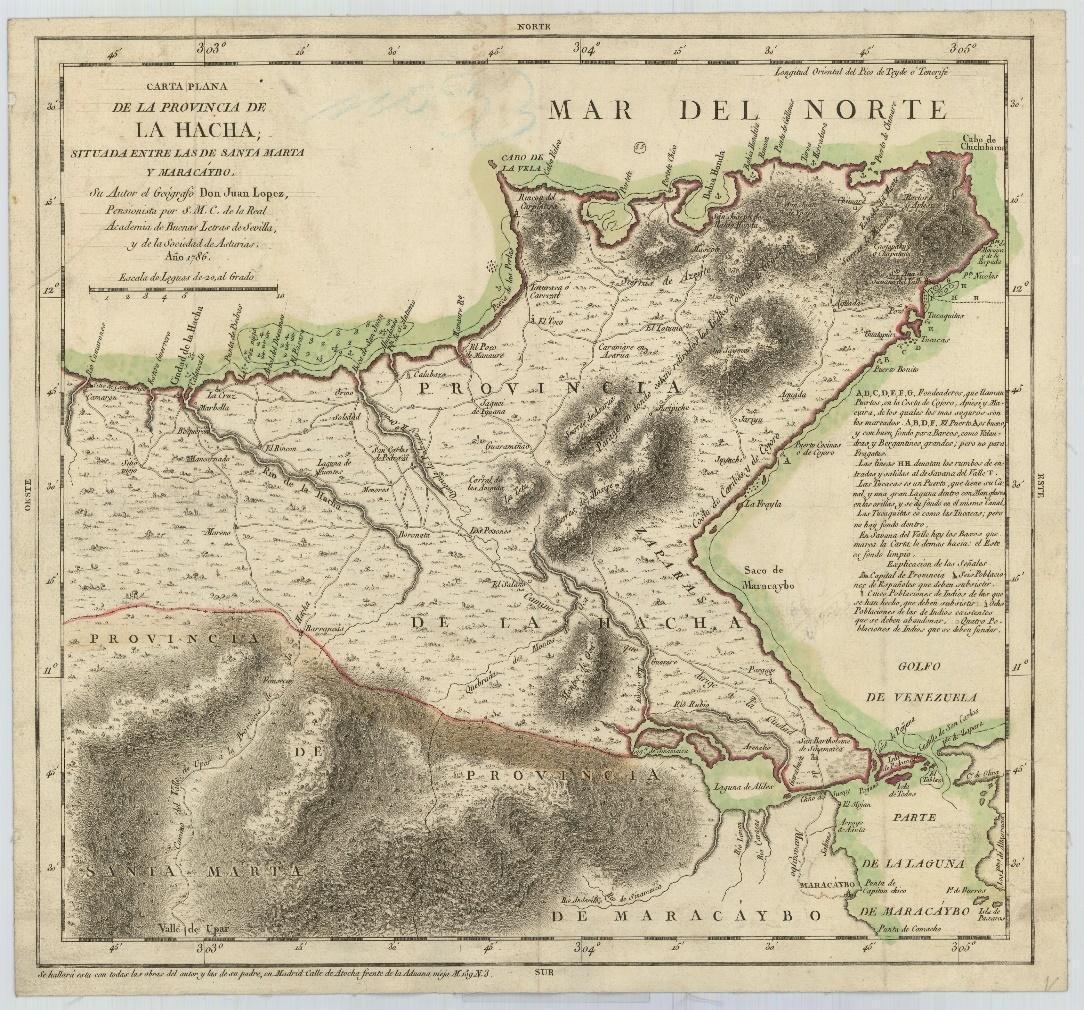

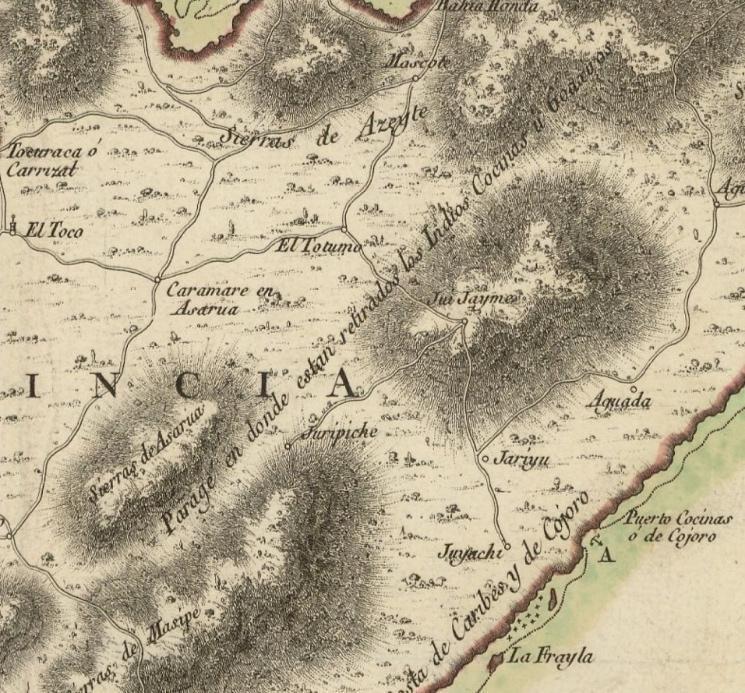

Other maps produced in the 1770s and 1780s, such as Antonio de Arévalo’s Mapa de la Costa de la provincia de Santa Marta con las bahías (see fig. 18) from the late 1770s and Juan López’s 1786 Carta plana de la provincia de el Hacha situada entre las de Santa Marta y Maracaybo (see fig. 20), show the presence of Cocina and Guajiro (Wayúu) Indians in the Peninsula and the Spanish authorities’ efforts to control them. For instance, the legend on López’s map talks about eight Indigenous settlements that must be abandoned. Such a plan to “abandon” settlements was possibly a plan to forcefully move Indigenous people into assigned reducciones.

Figure 18. Antonio de Arévalo, Mapa de la costa de la provincia de Santa Marta con las bahías, Rios y Sitios, (1770, Cartagena de Indias). Read more

Figure 19. Detail of the Guajira Peninsula in Arévalo, Mapa de la costa de la Provincia de Santa Marta con las bahías.

Figure 20. Juan López, Carta plana de la Provincia de la Hacha situada entre las de Santa Marta y Maracaybo (1786). Read more

Figure 21. Detail of the Guajira Peninsula in López, Carta plana de la Provincia de la Hacha situada entre las de Santa Marta y Maracaybo.

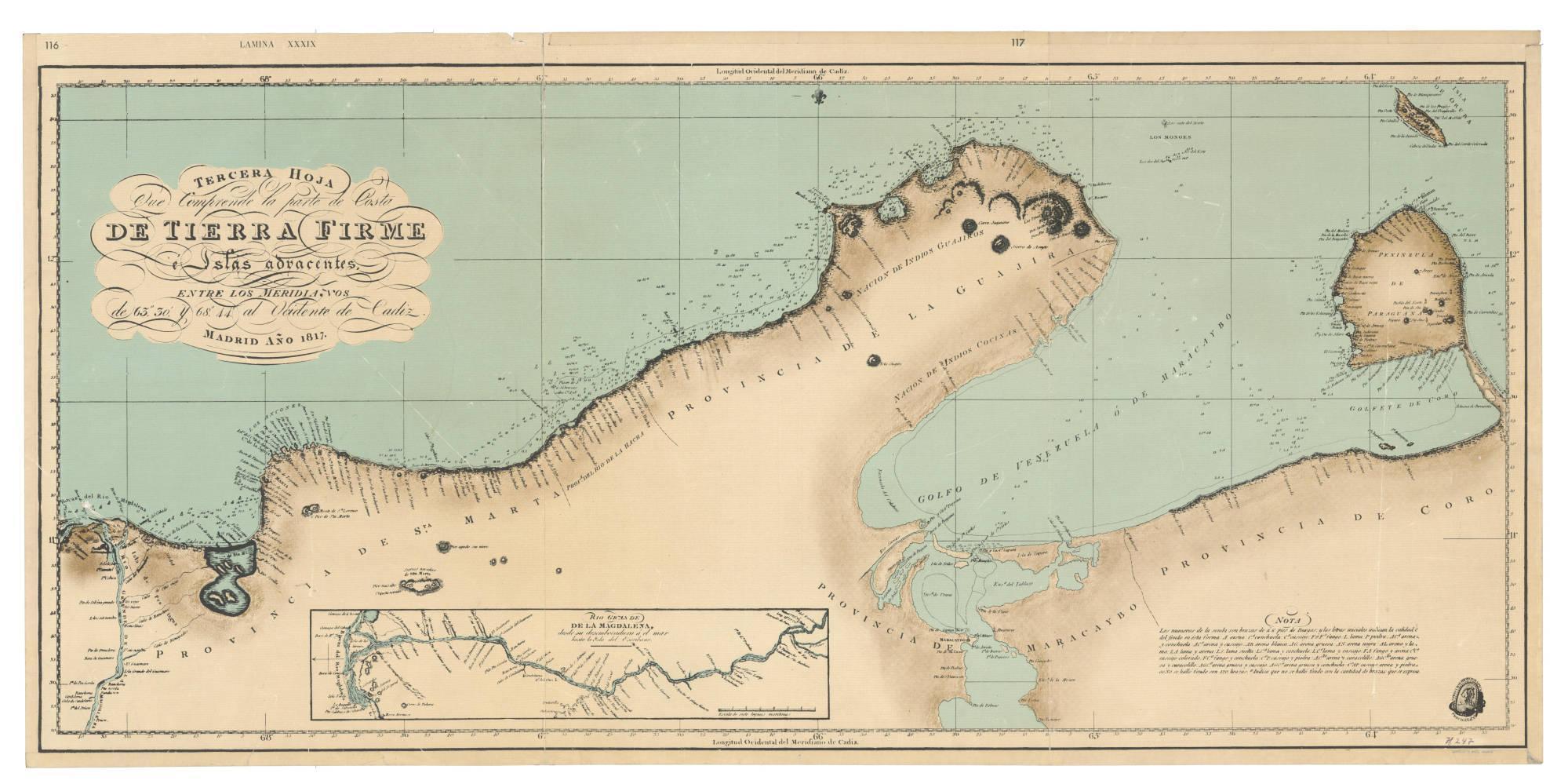

The 1800s and the republican era: Joaquin Francisco Fidalgo’s 1817 Tierra Firme e islas adyacentes (see fig. 22) shows territories inhabited by “Nation of Indios Guajiros” and “Nation of Indios Cocinas” but does not offer much more information about the Crown’s plans with regards to the Indigenous people of the Guajira. Yet, the fact that Fidalgo would refer to these Indigenous peoples as Nations is telling of their presence and organization in the area.

Figure 22. Joaquín Francisco Fidalgo, Tierra firme e islas adyacentes (1817, Madrid). Read more

Figure 23. Detail of the Guajira Peninsula in Fidalgo, Tierra firme e islas adyacentes.

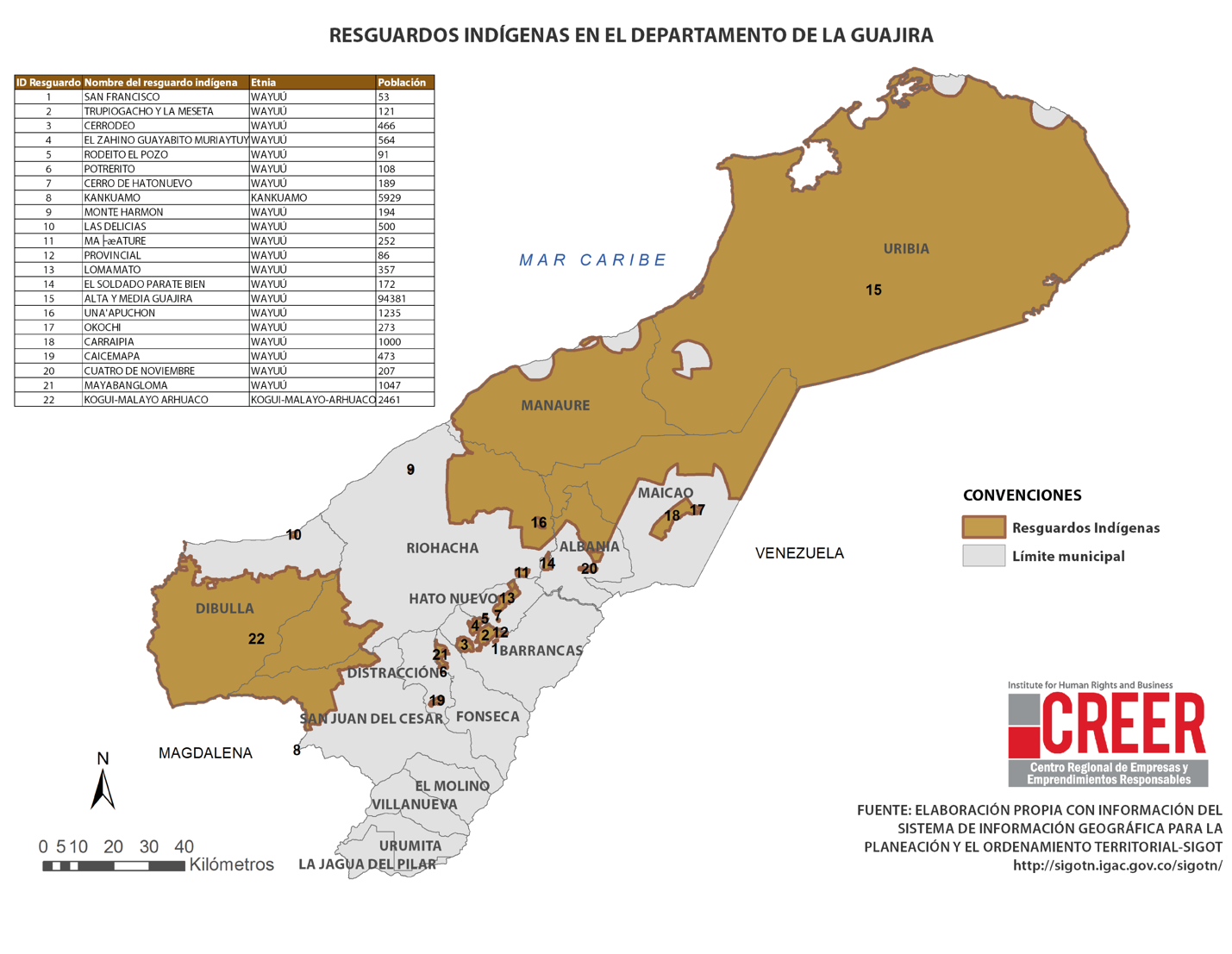

With the advent of new republican nations, most maps simply stopped referring to Indigenous peoples and their territories. After the 1820s, hardly any map alluded to the Indigenous people of the Guajira. It was only towards the late 20th century that maps began to represent, once again, Wayúu territories.

In the present, the Wayúu people are the largest Indigenous group in both Colombia and Venezuela.14 On the Colombian side of the Peninsula, in the Department (Province) of La Guajira, approximately 45% of the Department’s population are Wayúu people. In the Province of Zulia in Venezuela, close to 8% of its inhabitants are Wayúu.15

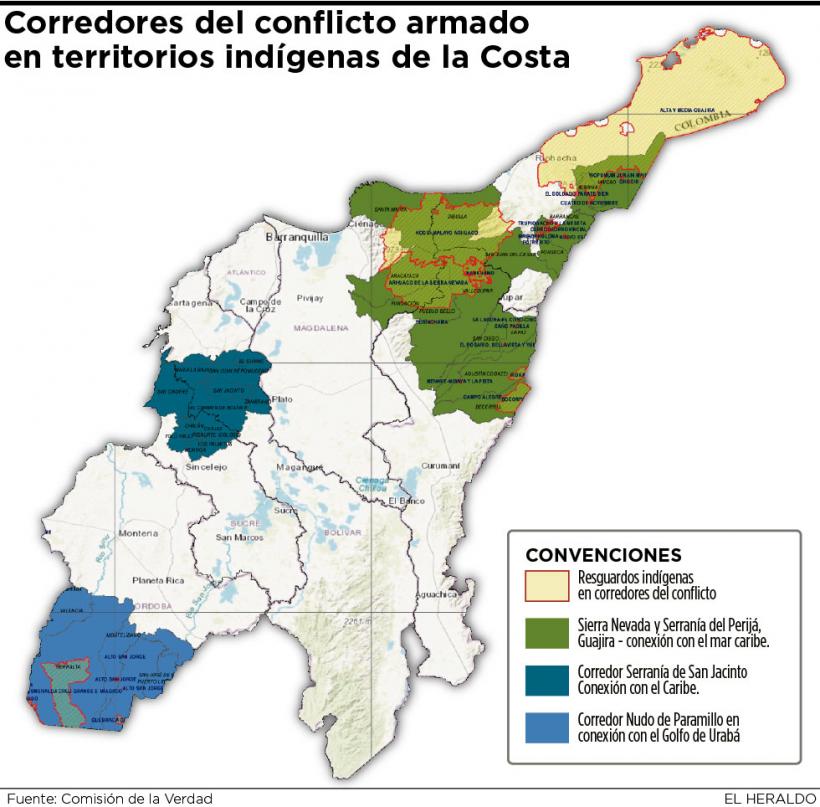

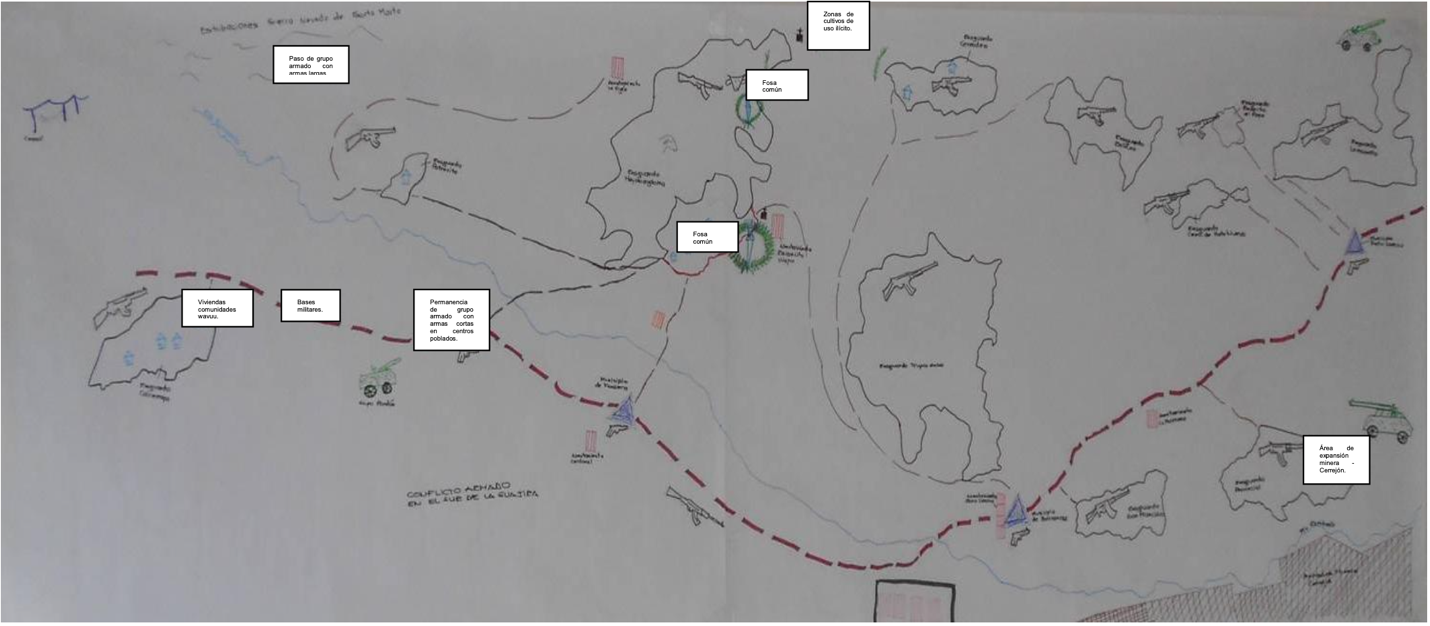

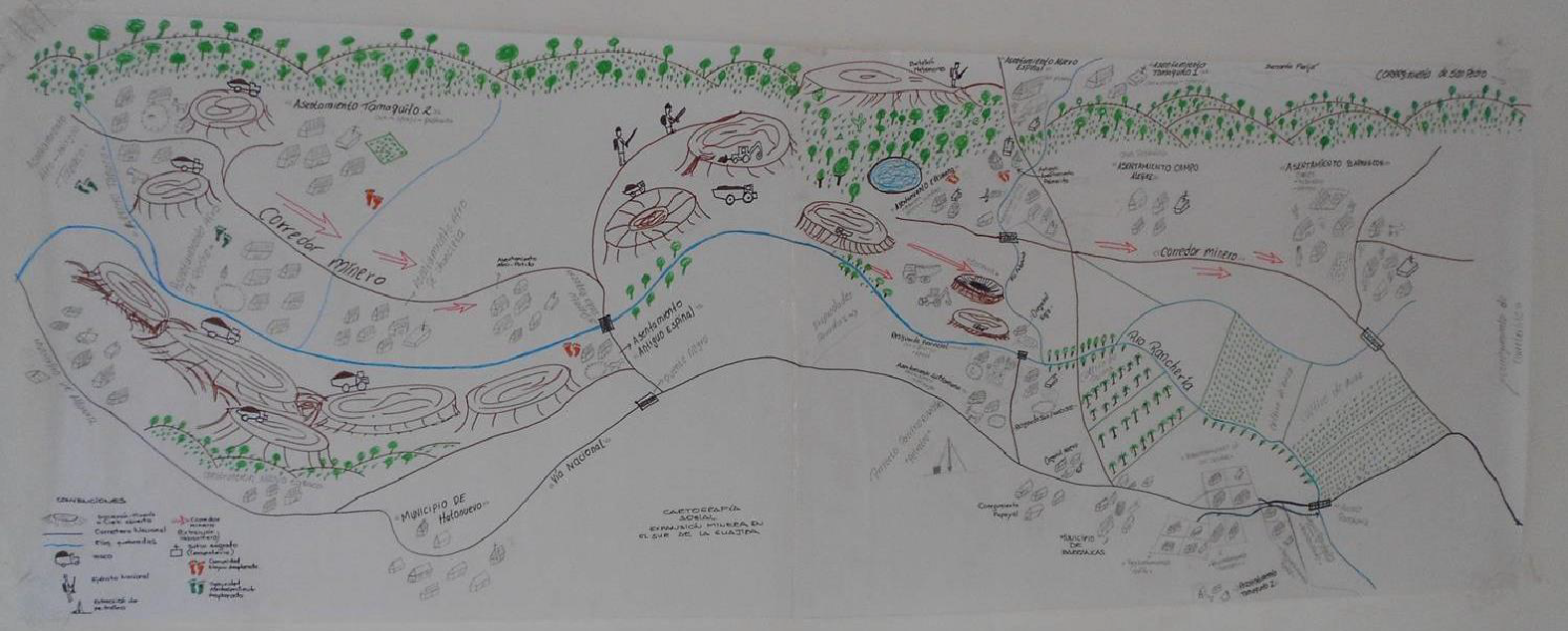

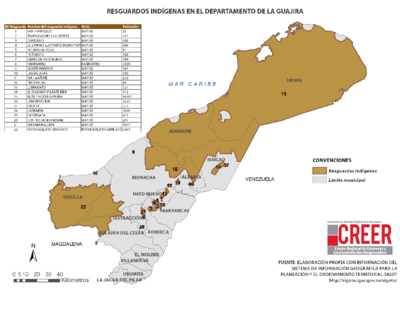

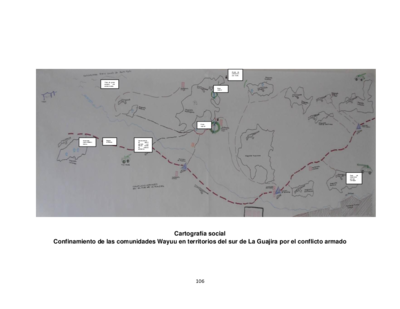

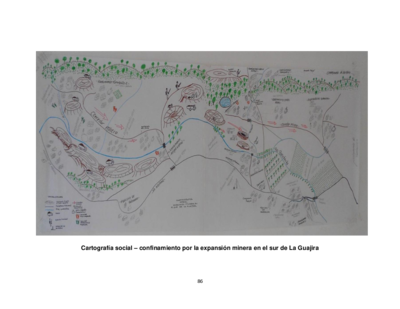

The Wayúu claim that their ancestral lands include the Guajira Peninsula, the western banks of Lake Maracaibo, and the proximities to the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta and the Serranía del Perijá. Although resguardos have been granted to Wayúu communities as well as to Arhuaco, Kankuamo, Kogui, and Wiwa communities that inhabit the Guajira (see fig. 24), these Indigenous groups argue that their territories and culture are under threat by the expansion of mining and energy activities and the presence of illegal armed actors.16 Additionally, the Indigenous people of the Guajira are also at risk because many of them live under precarious conditions, many of the region’s schools and homes lack steady electricity and sufficient drinking water, and the Wayúu have limited access to bilingual education.17 As the Wayúu’s own social cartography shows (see figs. 26, 27), the territories they consider sacred and ancestral along with their traditional grazing lands and routes are now threatened by the expansion of mining projects and armed actors.

Figure 24. Map showing indigenous reservations (“resguardos”) in the Guajira. “Resguardos Indígenas en el Departamento de la Guajira,” Centro Regional de Empresas y Emprendimientos Responsables (CREER), Geo EISI - Información Referenciada sobre los impactos en derechos humanos en Colombia – Guajira. Read more

Figure 25. Map showing corridors of armed conflict in indigenous territories. Jennyfer Solano, “Corredores del conflicto armado en territorios indígenas de la Costa,” El Heraldo, October 25, 2020.

Figure 26. Social cartography map showing confinement of Wayúu communities in territories of southern La Guajira due to armed conflict. Eisat’ta akuai’pa (proteger y salvaguardar). Plan Salvaguarda Wayuu. Zona Sur de la Guajira. (Fonseca, Distracción, Barrancas, Hatonuevo). Resguardo Indígena de Mayabangloma-Ministerio del Interior (2014), 106.

Figure 27. Social cartography map showing confinement due to mining expansion in southern La Guajira. Eisat’ta akuai’pa (proteger y salvaguardar). Plan Salvaguarda Wayuu. Zona Sur de la Guajira. (Fonseca, Distracción, Barrancas, Hatonuevo). Resguardo Indígena de Mayabangloma-Ministerio del Interior (2014), 86. Read more

Bibliography

Alcácer, Fray Antonio de, O.F.M. Las misiones capuchinas en el Nuevo Reino de Granada hoy Colombia. Chía: Ediciones Seminario Seráfico Misional Capuchino, 1959.

Barrera Monroy, Eduardo. Mestizaje, comercio y resistencia. La Guajira en la segunda mitad del siglo XVIII. Bogotá: Instituto Colombiano de Antropología e Historia, 2000.

Centro Regional de Empresas y Emprendimientos Responsables (CREER). “Resguardos Indígenas en el Departamento de la Guajira.” Geo EISI - Información Referenciada sobre los impactos en derechos humanos en Colombia - Guajira. https://www.creer-ihrb.org/_files/ugd/134a42_7695a003cf8f4411bcae5f720e305e57.pdf.

Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadísticas (DANE). “Informes de Estadística Sociodemográfica Aplicada.” 2021. http://www.dane.gov.co/files/investigaciones/poblacion/informes-estadisticas-sociodemograficas/2021-09-24-Registro-Estadistico-Pueblo-Wayuu.pdf.

Erbig, Jeffrey. Where Caciques and Mapmakers Met: Border Making in Eighteenth-Century South America. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2020.

Kagan, Richard. Urban Images of the Hispanic World, 1493–1793. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000.

Lopes de Carvalho, Francismar Alex. “Mapmaking and Sovereignty Building: Francisco Requena and the Late Eighteenth-Century Boundary Demarcation Commissions.” Hispanic American Historical Review 102, no. 2 (2022): 191–221.

Madrid, Marcela, et al. “Crónica: Seis años de elefantes blancos y una nación sin agua.” Dejusticia. February 3, 2023. https://www.dejusticia.org/cronica-seis-anos-de-elefantes-blancos-y-una-nacion-sin-agua/.

Ministerio de Cultura de Colombia, Dirección de Poblaciones. “Caracterización de los pueblos indígenas de Colombia. Wayúu: Gente de arena, sol y viento.” 2016. https://www.mincultura.gov.co/prensa/noticias/Documents/Poblaciones/PUEBLO%20WAY%C3%9AU.pdf.

Muñoz, Santiago, and Sebastián Díaz Ángel. “El Plan geográfico del virreinato de Santafé: la comunidad política en el mapa de Francisco Moreno y Escandón.” Boletín Cultural y Bibliográfico 55, no. 100 (2021): 118–136.

Palmar Uriana, Dayanna Gladys. “La binacionalidad del pueblo wayuu: la deuda pendiente de Venezuela y Colombia.” Dejusticia. February 8, 2023. https://www.dejusticia.org/column/la-binacionalidad-del-pueblo-wayuu-la-deuda-pendiente-de-venezuela-y-colombia-1/.

Polo Acuña, José Trinidad. “Los Wayúu y los Cocina: dos caras diferentes de una misma moneda en la resistencia indígena en la Guajira, siglo XVIII.” Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y de la Cultura, no. 26 (1999): 7–29.

Polo Acuña, José Trinidad. Etnicidad, conflicto social y cultura fronteriza en la Guajira, 1700–1850. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes-Observatorio del Caribe Colombiano, 2005.

Polo Acuña, José Trinidad. Indígenas, poderes y mediaciones en La Guajira en la transición de la Colonia a la República (1750–1850). Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes, 2012.

Restrepo Olano, Margarita. “Un ejemplo de relaciones simbióticas en la Guajira del siglo XVIII. Historia de una sublevación bajo el liderazgo del cacique Cecilio.” Revista Complutense de Historia de América 39 (2013): 177–201.

Saether, Steinar A. Identidades e independencia en Santa Marta y Riohacha. 1750–1850. Bogotá: Instituto Colombiano de Antropología e Historia, 2005.

Safier, Neil. Measuring the New World: Enlightenment Science and South America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Solano, Jennyfer. “Corredor del conflicto armado en territorios indígenas de la Costa.” El Heraldo, October 25, 2020. https://www.elobservador.com.co/2020/11/11/corredor-del-conflicto-armado-en-territorios-indigenas-de-la-costa/

List of Figures

Figures 1, 22–23. Fidalgo, Joaquín Francisco. Tierra firme e islas adyacentes. Madrid: 1817. Banco de la República – Biblioteca Virtual. Cartografía histórica, H247. https://babel.banrepcultural.org/digital/collection/p17054coll13/id/467.

Figures 2–3. Münster, Sebastian. Tabula Novarum Insularum, Quas Diversis Respectibus Occidentales & Indianas uocant. Basle: 1550. Barry Lawrence Ruderman Map Collection, Stanford University, Stanford, CA. https://exhibits.stanford.edu/ruderman/catalog/mz230kn1495.

Figures 4–5. Mercator, Gerhard et al. America Meridionalis. Amsterdam: 1623. David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, Stanford University, Stanford, CA. https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~329282~90097769:America-Meridionalis--Inset--Cusco-.

Figures 6–7. Sanson d’Abbeville, Nicolas. Amerique Meridionale. Paris: 1650. JCB Map Collection, The John Carter Brown Library, Providence, RI. Accessed February 26, 2022. https://jcb.lunaimaging.com/luna/servlet/detail/JCBMAPS~1~1~3361~101626:Amerique-Meridionale-par-N--Sanson-?sort=normalized_date%2Cfile_name%2Csource_author%2Csource_title.

Figures 8–9. Jaillot, Alexis Hubert. L’Amerique Meridionale Divisée en ses Principales Parties. Presenté à Monseigneur le Duc de Bourgogne. Paris: 1697. JCB Map Collection, The John Carter Brown Library, Providence, RI. https://jcb.lunaimaging.com/luna/servlet/s/731wqz.

Figures 10–11. Morato Aparicio, José, and Francisco Moreno y Escandón. Plan geográfico del virreinato de Santa Fe de Bogotá. Santafé de Bogotá: 1772. Maps, Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia, MD-MC-Fmapoteca_262_frestrepo_36 – University of Manchester. Accessed March 7, 2023. https://minerva.manchester.ac.uk/new-granada/items/show/15.

Figures 12–14. Arévalo, Antonio de. Mapa general de la provincia de indios guagiros que llaman del Hacha. Cartagena de Indias: 1773. Archivo General Militar de Madrid, Biblioteca Virtual de Defensa, COL-16/6, Bar code: 2120182. https://bibliotecavirtual.defensa.gob.es/BVMDefensa/es/consulta/registro.do?id=113315.

Figures 15–17. Arévalo, Antonio de. Mapa general de la Provincia de la Hacha: Situada entre las de Sta. Marta, y Maracaibo para inteligencia de su Estencion y limites. Rio de la Hacha: 1776. Archivo General Militar de Madrid, Biblioteca Virtual de Defensa, COL-16/1, Bar code: 2120159. https://bibliotecavirtual.defensa.gob.es/BVMDefensa/es/consulta/registro.do?id=113311.

Figures 18–19. Arévalo, Antonio de. Mapa de la costa de la provincia de Santa Marta con las bahías, Rios y Sitios. Cartagena de Indias: 1770. Archivo General Militar de Madrid, Biblioteca Virtual de Defensa, COL-6/1, Bar code: 2119961. https://bibliotecavirtual.defensa.gob.es/BVMDefensa/es/consulta/registro.do?id=113294.

Figures 20–21. López, Juan. Carta plana de la Provincia de la Hacha situada entre las de Santa Marta y Maracaybo. 1786. Archivo General Militar de Madrid, Biblioteca Virtual de Defensa, COL-5/6; Bar code: 2121636. https://bibliotecavirtual.defensa.gob.es/BVMDefensa/es/consulta/registro.do?id=113343.

Figure 24. “Resguardos Indígenas en el Departamento de la Guajira,” Centro Regional de Empresas y Emprendimientos Responsables (CREER), Geo EISI - Información Referenciada sobre los impactos en derechos humanos en Colombia – Guajira. https://creer-ihrb.org/geo-eisi-guajira/

Figure 25. Solano, Jennyfer. “Corredor del conflicto armado en territorios indígenas de la Costa.” El Heraldo, October 25, 2020. https://www.elobservador.com.co/2020/11/11/corredor-del-conflicto-armado-en-territorios-indigenas-de-la-costa/.

Figure 26. “Cartografía social – Confinamiento de las comunidades Wayúu en territorios del sur de La Guajira por el conflicto armado." Eisat’ta akuai’pa (proteger y salvaguardar). Plan Salvaguarda Wayuu. Zona Sur de la Guajira (Fonseca, Distracción, Barrancas, Hatonuevo). Resguardo Indígena de Mayabangloma - Ministerio del Interior (2014), 106. https://www.mininterior.gov.co/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/pueblo_wayuu_sur_de_la_guajira_-_diagnostico_comunitario_0.pdf.

Figure 27. “Cartografía social – Confinamiento por la expansión minera en el sur de La Guajira.” Eisat’ta akuai’pa (proteger y salvaguardar). Plan Salvaguarda Wayuu. Zona Sur de la Guajira (Fonseca, Distracción, Barrancas, Hatonuevo). Resguardo Indígena de Mayabangloma - Ministerio del Interior (2014), 86. https://www.mininterior.gov.co/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/pueblo_wayuu_sur_de_la_guajira_-_diagnostico_comunitario_0.pdf.

The Wayúu speak an Arawak dialect called Wayuunaiki. In Wayuunaiki, “wayúu” means “people” and “guajira” means “our land.” (“Caracterización de los pueblos indígenas de Colombia. Wayúu: Gente de arena, sol y viento. Ministerio de Cultura de Colombia.” Dirección de Poblaciones. 2016. https://www.mincultura.gov.co/prensa/noticias/Documents/Poblaciones/PUEBLO%20WAY%C3%9AU.pdf.) ↩︎

For more information, see: José Trinidad Polo Acuña, Indígenas, poderes y mediaciones en La Guajira en la transición de la Colonia a la República (1750–1850) (Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes, 2012); José Trinidad Polo Acuña, Etnicidad, conflicto social y cultura fronteriza en la Guajira, 1700–1850 (Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes-Observatorio del Caribe Colombiano, 2005); Steinar A. Saether, Identidades e independencia en Santa Marta y Riohacha. 1750–1850 (Bogotá: Instituto Colombiano de Antropología e Historia, 2005); Eduardo Barrera Monroy. Mestizaje, comercio y resistencia. La Guajira en la segunda mitad del siglo XVIII (Bogotá: Instituto Colombiano de Antropología e Historia, 2000). ↩︎

On the possible reasons for the decimation of the Cocina and the endurance of the Wayúu, Polo Acuña explains that the Wayúu adapted more efficiently to the arrival of European culture and economic relations. The Wayúu, contrary to the Cocina, embraced livestock ranching and trade with Spanish and other Europeans. Likewise, the Wayúu’s closer contact with Europeans led to a greater level of biological and cultural mestizaje* that, according to Polo Acuña, helps explain the survival of the Wayúu. (José Trinidad Polo Acuña, “Los Wayúu y los Cocina: dos caras diferentes de una misma moneda en la resistencia indígena en la Guajira, siglo XVIII,” Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y de la Cultura, no. 26 (1999): 7–29.) ↩︎

There are several different copies of this map with different dates and colors. The map has, on its bottom-left corner, an ‘Europeanized’ image of Cuzco. (For more information on the image of Cuzco, see: Richard Kagan, Urban Images of the Hispanic World, 1493–1793 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000).) ↩︎

For more information, see: Francismar Alex Lopes de Carvalho, “Mapmaking and Sovereignty Building: Francisco Requena and the Late Eighteenth-Century Boundary Demarcation Commissions”, Hispanic American Historical Review 102, no. 2 (2022): 191–221; Neil Safier, Measuring the New World: Enlightenment Science and South America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008); Jeffrey Erbig, Where Caciques and Mapmakers Met: Border Making in Eighteenth-Century South America (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2020); Santiago Muñoz and Sebastián Díaz Ángel, “El Plan geográfico del virreinato de Santafé: la comunidad política en el mapa de Francisco Moreno y Escandón”, Boletín Cultural y Bibliográfico 55, no. 100 (2021): 118–136. ↩︎

Polo Acuña, Indígenas, poderes y mediaciones en La Guajira. ↩︎

Polo Acuña, Indígenas, poderes y mediaciones en La Guajira; Polo Acuña, Etnicidad, conflicto social y cultura fronteriza; Saether, Identidades e independencia; Barrera Monroy, Mestizaje, comercio y resistencia. ↩︎

Fray Antonio de Alcácer O.F.M., Las misiones capuchinas en el Nuevo Reino de Granada hoy Colombia (Chía: Ediciones Seminario Seráfico Misional Capuchino, 1959). ↩︎

Polo Acuña, Indígenas, poderes y mediaciones en La Guajira; Polo Acuña, Etnicidad, conflicto social y cultura fronteriza; Saether, Identidades e independencia; Barrera Monroy, Mestizaje, comercio y resistencia; Margarita Restrepo Olano, “Un ejemplo de relaciones simbióticas en la Guajira del siglo XVIII. Historia de una sublevación bajo el liderazgo del cacique Cecilio”, Revista Complutense de Historia de América 39 (2013): 177–201. ↩︎

For more information on Moreno y Escandón’s map, see: Muñoz and Díaz Ángel, “El Plan geográfico del virreinato de Santafé”. ↩︎

“Estos pueblos y sitios han sido incendiados últimamente por los indios rebeldes” (Moreno y Escandón, Francisco. Aparicio Morata and Moreno y Escandón, Plan geográfico del virreinato de Santa Fe de Bogotá.) ↩︎

“…en el tiempo de la mencionada sublevación, todos los Yndios de la Provincia y los Yndios sublevados quedaron arruinados demare que se quemaron 60 poblaciones entre lugares, hattos, pueblos, y casserias o haciendas; Murieron muchos Yndios y de los Españoles se cuentan 82 vidas muertos.” (Antonio de Arévalo, Mapa general de la provincia de indios guagiros que llaman del Hacha (1773, Cartagena de Indias), Archivo General Militar de Madrid, Bar code: 2120182, https://bibliotecavirtual.defensa.gob.es/BVMDefensa/es/consulta/registro.do?id=113315.) Mapa generl. de la prova de Yndios Guagiros que llaman del Hacha [sic] : Situada entre las de Sta. Marta y Maracaibo, para la inteligencia de su exttenssion y limites, y la de colocacion de los nuevos pueblos a que se redugeron ultimamente los indios sublevados en el año de 1769, y las de otros que se deven fundar de yndios y de españoles en el resstto de la provincia para consseguir y mantener la pacificacion general de ella segun las órdenes del Exmo. Sr. Virrey de esstte nuevo reino Dn. Manuel Guirion acompañado de un discurso en el que se manifiesstta su essttado anttiguo, el pressentte y en el podra ponersse en adelantte ↩︎

“Que en las Sierras de Macuira… es el terreno en donde, en seis sangrientas funciones dadas a los Yndios sublevados, se han castigado a estos con quinientos Españoles, siendo ellos mas de quatro mil bien armados. Haviendoles también quemado todas sus cassas y arrasado todas sus sementeras, y obligadoles a abandonar enteramente toda aquella extencion del país que ocupaban de modo que al fin de la campaña, no se hallaron en el ya enemigos que vencer…” (Antonio de Arévalo, Mapa general de la Provincia de la Hacha: Situada entre las de Sta. Marta, y Maracaibo para inteligencia de su Estencion y limites, (Rio de la Hacha: 1776), Archivo General Militar de Madrid, emphasis added. https://bibliotecavirtual.defensa.gob.es/BVMDefensa/i18n/consulta/registro.do?control=BMDB20200484028 Mapa general de la Provincia de la Hacha : Situada entre las de Sta. Marta, y Maracaibo para inteligencia de su Estencion y limites de la situación de los nuevos pueblos a los que se redujeron en principios del año 1773 los indios goagiros, sublevados en el de 69 y la de otros que se han fundado, e igualmente las nuevas fundaciones de españoles hechas a fin de conseguir la pacificacion general de ella, y su conservacion, segun el proyecto formado para este efecto por su Comandte. Genl. el Briga. de ingenieros director Dn. Antonio de Arebalo, quien al presente propone al Exmo. Sor. Virrey Dn. Manl. Antonio de Florez lo que tiene indispensable se ejecute para conseguir la otra pacificacion Gnl., y grande ahorro de gastos a la Real Hacienda ↩︎

In the Colombian 2018 census, 380,460 people identified as Wayúu. (“Informes de Estadística Sociodemográfica Aplicada.” Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadísticas (DANE), 2021. http://www.dane.gov.co/files/investigaciones/poblacion/informes-estadisticas-sociodemograficas/2021-09-24-Registro-Estadistico-Pueblo-Wayuu.pdf). For more information about the binational character of the Wayúu and the challenges this brings about, please see: Dayanna Gladys Palmar Uriana, “La binacionalidad del pueblo wayuu: la deuda pendiente de Venezuela y Colombia”, Dejusticia, February 8, 2023, https://www.dejusticia.org/column/la-binacionalidad-del-pueblo-wayuu-la-deuda-pendiente-de-venezuela-y-colombia-1/). ↩︎

“Caracterización de los pueblos indígenas de Colombia. Wayúu: Gente de arena, sol y viento”, Ministerio de Cultura de Colombia, Dirección de Poblaciones. 2016. https://www.mincultura.gov.co/prensa/noticias/Documents/Poblaciones/PUEBLO%20WAY%C3%9AU.pdf. ↩︎

Jennyfer Solano, “Corredor del conflicto armado en territorios indígenas de la Costa,” El Heraldo, October 25, 2020, https://www.elobservador.com.co/2020/11/11/corredor-del-conflicto-armado-en-territorios-indigenas-de-la-costa/. Corredor del conflicto armado en territorios indígenas de la Costa ↩︎

Marcela Madrid, et al., “Crónica: Seis años de elefantes blancos y una nación sin agua”, Dejusticia, February 3, 2023, https://www.dejusticia.org/cronica-seis-anos-de-elefantes-blancos-y-una-nacion-sin-agua/. ↩︎

!["Plan geografico del Vireynato de Santafe de Bogota;Nuevo Reyno de Granada;que manifiesta su demarcación territorial;islas;rios principales;provincias;y plazas de armas;lo que ocupan indios barbaros;y naciones extrangeras;demostrando los cõfines de los dos Reynos de Lima;México;y establecimientos de Portugal sus lindantes: con notas;historiales del ingreso anual de sus rentas reales;y noticias relativas a su actual estado civil;político;y militar [material cartográfico] / formando en servicio del Rey nro. sor. por el D. D. Francisco Moreno y Escandón;fiscal protector de la Real Audiencia de Santa Fe;y juez conservador de rentas;lo delineo D. Joseph Aparicio Morata;año de 1772;gobernando el reyno el excmo. sor. Bailio Frey D. Pedro Messia de la Cerda"](https://dnet8ble6lm7w.cloudfront.net/maps/CNT/CNT0007.jpg)

![Mapa generl. de la prova de Yndios Guagiros que llaman del Hacha [sic] : Situada entre las de Sta. Marta y Maracaibo, para la inteligencia de su exttenssion y limites, y la de colocacion de los nuevos pueblos a que se redugeron ultimamente los indios sublevados en el año de 1769, y las de otros que se deven fundar de yndios y de españoles en el resstto de la provincia para consseguir y mantener la pacificacion general de ella segun las órdenes del Exmo. Sr. Virrey de esstte nuevo reino Dn. Manuel Guirion acompañado de un discurso en el que se manifiesstta su essttado anttiguo, el pressentte y en el podra ponersse en adelantte](https://dnet8ble6lm7w.cloudfront.net/maps/COL/COL0090.jpg)