Abstract

For more than three decades, local community members, scientists, and organizations have worked tirelessly to protect the cloud forest in the Intag Valley, Imbabura Province, Ecuador; home to the longnose harlequin frog. After a long legal dispute, the Constitutional Court ruled in favor of those supporting the frog and its ecosystem. The discovery of this supposedly extinct frog and other considerations regarding the ecosystem played a crucial role in the cancellation of Enami EP and Codelco mining permits in the Valley.

Three Decades of Resistance

In a 12-minute documentary entitled “Defending the Íntag Valley: 30 Years of Community Resistance,” Carlos Zorrilla1, a local community leader in the Intag Valley, Imbabura Province, refers to the major environmental campaigns against mineral exploration and exploitation in this part of Ecuador. The Intag Valley, located in the cloud forest mountains, is home to approximately 15,000 people who rely on agriculture and cattle farming. The documentary exhibits this special type of ecosystem, along with some bird species and a lizard, while Zorrilla’s speech is accompanied by a piano. “We have identified 69 species of animals and plants that are on the brink of extinction,” he claims, emphasizing the importance and urgency of the term “on the brink of extinction”; as local residents have opposed the mining projects since the 1990s, when the first mining company arrived in the Íntag Valley in search of copper, yet the legal battle commenced in 2011 and lasted for nine years.

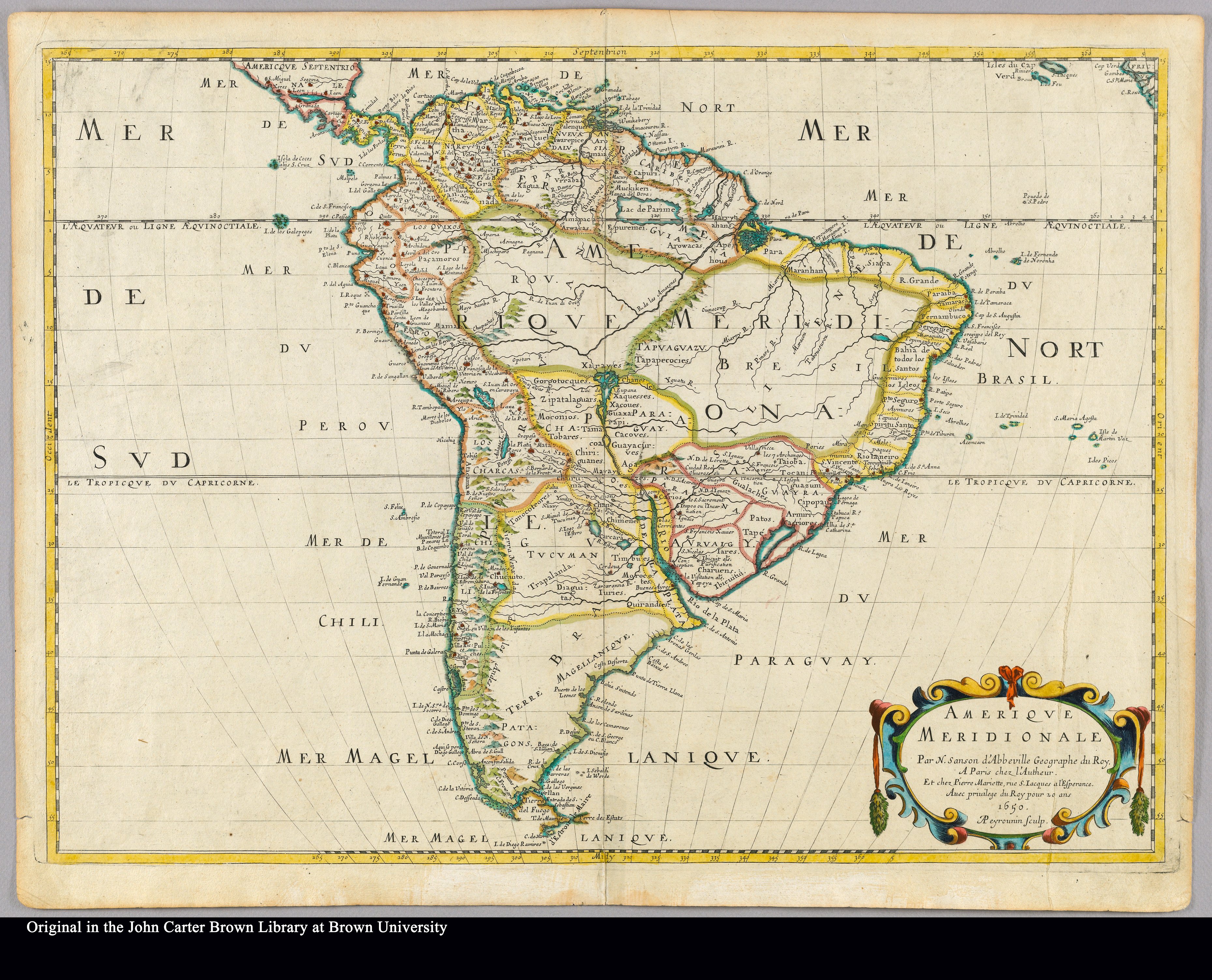

Imbabura, a province in northern Ecuador, holds great historical significance due to its role as a transit hub during colonial times. While most of its population is mestizo residing in the high mountains, there is evidence of an estimated 25% presence of Indigenous communities in this province as well. These communities struggle to protect their ancestral lands, particularly in the Ecuadorian Amazon region, as shown by the leading cases of A’I Cofán de Sinangoe in 2018 and Waorani in 2019. These cases highlight the brave efforts of Indigenous communities in Ecuador to safeguard their lands from hydrocarbon exploration and exploitation, underscoring the importance of prior consultation. In turn, the legal victory of the peasant communities of Intag Valley sets a precedent for other groups to be consulted and considered. In this case, the alliance with other species has been key in supporting the arguments presented in court.

In the early 1990s, Zorrilla established a group of local park rangers to protect the spectacled bear, South America’s only known bear species. The group eventually evolved into a local organization called Decoin, led by Zorrilla. Decoin´s primary goals in 1995 were to preserve the unique biodiversity in the Intag area of Northwestern Ecuador and to oppose incoming corporations searching for metals.

It was precisely during this time that a mining development phase started in Ecuador under the financial support of the World Bank. The Prodeminca project —intended to provide technical assistance in mining development and environmental control—, was launched in 1993 as part of that loan-funded program, facing strong opposition from Decoin and the Asociación de Caficultores Orgánicos Río Íntag (AACRI). Both groups contested the project and urged the World Bank for an inspection. In 2001, the project was terminated, yet other companies entered the Valley. The first was Bishimetals, which faced strong opposition from local communities and eventually abandoned the area after their equipment was burned. A few years later, in 2004, Ascendant Cooper —a Canadian corporation— launched its operations, facing significant resistance from the local communities. The situation escalated until 2009, when it turned into violent confrontations, after which the company finally decided to leave Ecuador. Lastly, in 2011 the Llurimagua mining concession was granted to Enami EP, Ecuador’s national mining company, in association with Codelco, Chile’s national copper mining company. Community resistance led to the use of police force during the exploratory phase in 2014, following initial failed attempts at socializing the project.

The initial phase of mining is often thought to have minimal environmental impact. However, in 2017, researchers Aurélie Chopard and William Sacher conducted a study in Íntag on the impact of mining on water, reporting that the activity conveyed a significant contamination risk. Their findings revealed that rocks at the site contained arsenic, copper, and molybdenum; and that the drilling process led to water acidification. Furthermore, in a surface-collected sample they detected two potentially highly contaminating minerals, pyrite and tennantite. Pyrite is known to cause acid mine drainage, with severe and irreversible effects on ecosystems and human health. Tennantite, in turn, is a hazardous reactive mineral containing arsenic and antimony.2

The 2014 Environmental Impact Study found that each drilling post can reach depths of nearly a mile. The two most common methods for extracting copper are using explosives or hydraulic perforations to break the mantle. Following this process, rock samples are examined to identify the presence of copper deposits.3 The use and disposal of water, as well as the removal of other chemicals from the rocks, bear a significant environmental risk. In addition to this, water from the exploration wells was being discharged into the rivers without any treatment, as confirmed by the community water quality monitoring group.4

Frogs in the Cloud Forest

Over the years, community resistance against mining projects has taken various forms. It wasn’t just about opposing or confronting the projects through legal proceedings. Local communities also resisted by establishing natural reserves. In this regard, 38 civil reserves containing garden centers were created to restore heavily deforested areas in the biodiversity hotspot where the Ecuadorian Chocó meets the Tropical Andes.5

These forests have been the habitat of various species, and it was quite a surprise when scientists came across a frog that was believed to have been extinct for years. The Atelopus longetrostis, also known as the longnose harlequin frog, had been spotted for the last time in 1989. The first record in Western science about this particular species dates back to 1868, documented by a young explorer named Edward Drinker Cope, who had joined the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. 6 Like some other species, the longnose harlequin frog managed to survive the test of time, to be later rediscovered in 2016 in Junín, Imbabura, in the very same place where the legal dispute took shape. Following this discovery, the frog was found in only one location. Scientists describe this frog as “a diurnal species with terrestrial and semiarboreal habits. It is mostly active during daylight, often spotted near water streams in evergreen forests, walking on open rocky shores. At night, it seeks refuge under rocks or rests on leaves close to the ground. This species breeds in streams.” The description makes it clear that any kind of mining exploration could significantly impact the frog’s survival.7

The longnose harlequin frog’s discovery cast light on the importance of the cloud forest ecosystem and its remarkable preservation over time, being capable of supporting life that was once thought to be extinct. While the court’s judgement underscores the importance of Nature’s rights and preserving biotic conditions, it is also crucial to acknowledge that the forest has been shaped and reshaped through interactions among people, trees, frogs, rivers, clouds, rocks, and other elements. These interactions show that resilience is a collective effort. Rediscovering the longnose harlequin frog 27 years after it was declared extinct by the scientific community is another powerful example of what resilience means in this context.8 It’s been nearly three decades since it all began. Protecting, fighting for, and resisting alongside the forest and all its inhabitants involves a fine balance of various factors. It can encompass serendipity, science, and collaboration, all working together toward a shared purpose.

References

Chopard, Aurélie y William Sacher, 2017, “Megaminería y agua en Intag: una evaluación independiente. Análisis preliminar de los potenciales impactos en el agua por la explotación de cobre a cielo abierto en Junín, zona de Intag, Ecuador”, Decoin.

Codelco Educa. “Extracción: Sacando la Materia Prima.”, 2019. https://www.codelcoeduca.cl/codelcoeduca/site/edic/base/port/extraccion.html.

Corte Constitucional del Ecuador, Sentencia No. 1149-19-JP/21 Juez ponente: Agustín Grijalva Jiménez

Fairfield Osborn, Henry. 1929. Biographical Memoir of Edward Drinker Cope 1840-1897. National Academy of Sciences. https://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/cope-edward.pdf.

Mongabay, “Defending the Intag Valley: 30 Years of Community Resistance.” November 20, 2020. Video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0-R7JCs_6j0.

Tapia, Elicio Eladio, Luis Aurelio Coloma, Gustavo Pazmiño-Otamendi & Nicolás Peñafiel, 2017. Rediscovery of the nearly extinct longnose harlequin frog Atelopus longirostris (Bufonidae) in Junín, Imbabura, Ecuador, Neotropical Biodiversity, 3:1, 157-167, DOI: 10.1080/23766808.2017.1327000

Zorrilla, Carlos, and Johanna Sydow. “Por qué Es Importante La Debida Diligencia Ambiental En Las Cadenas De Suministro De Minerales.” Germanwatch, November 1, 2020. https://co.boell.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/Fallstudie%20Ecuador_ES_final.pdf.

Carlos Zorrilla has founded more than six organizations and authored a book in 2009. An updated version was released in 2016 to assist other communities in resisting mining projects.: “Protecting Your Community From Mining and Other Extractive Operations: A Guide for Resistance”. ↩︎

Chopard and Sacher, Megaminería y agua en Intag. 2017 ↩︎

Codelco Educa, Extracción 2019, 12 ↩︎

Zorrila and Sydow, Porqué es importante la debida diligencia medioambiental, 13 ↩︎

Mongabay, Defending the Íntag Valley, 02:13 ↩︎

Fairfield, Biographical Memoir of Edward Drinker Cope 1929, 151 ↩︎

Tapia et.al., Rediscovery of the nearly extinct longnose harlequin frog, 158 ↩︎

Tapia et.al., 164 ↩︎